An otolith is pulled out of the brain cavity of a chinook salmon.

Britta Retzlaff Brennan

If you were to catch a salmon in Puget Sound, chances are you won’t be able to say exactly where that fish came from. That’s because salmon spawn in rivers and streams and then swim hundreds or even thousands of miles to the ocean to mature.

Some new research could help fisheries managers better protect salmon by studying their ear bones - that’s right, ear bones.

They're called otoliths and they help fish with balance and hearing. They come in different shapes and sizes, depending on the type of fish, but they share a common, very cool, growth pattern. Each year, the otolith adds a ring, just like a tree trunk. Those rings are incredibly valuable to scientists like Sean Brennan because they reveal where the fish spent time over the course of that year.

"It’s very similar to fingerprinting," said Brennan, a post doctoral researcher at the University of Washington. "But instead of using a fingerprint to determine who somebody is, what this does is it determines where a fish is from and which habitats it uses."

As it grows, the otolith absorbs trace elements, including strontium, which occurs naturally in rocks and the ocean. By measuring the ratios of strontium isotopes in the fish ear bones, and then comparing them to the ratios that have been measured throughout a watershed, scientists are able to tell where a fish spent time.

One of the many tributaries of the Upper Nushagak River, home to one of the largest wild chinook salmon runs in the world.

Sean Brennan, University of Washington

Sean Brennan mapped the strontium isotopes throughout Alaska's Nushagak River watershed, home to one of the largest chinook salmon runs in the world (and also home to the proposed site of the controversial Pebble Mine). He then gathered otoliths from 250 chinook salmon, which he caught at the mouth of the river, many miles from their spawning grounds. He was able to trace the salmon back to distinct regions of the watershed.

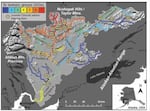

Sean Brennan mapped strontium isotope ratios in Alaska's Nushagak watershed. Then he broke them down into 7 different groups that shared the same ratios so that he could match them up with the ratios he found in the otoliths of adult salmon he caught at the mouth of the river.

Sean Brennan

Brennan found that 70 percent of the fish were originating from three specific parts of the upper watershed. He also found that 70 percent of the fish he sampled spent their first year in freshwater instead of migrating to the ocean right away.

Brennan says the level of detail needed to definitively say what percentage of the chinook run on the Nushagak would be affected by the Pebble Mine was not the focus of his research, but scientists need a way to figure out where fish come from. With that information they can begin to understand how habitat, fish movement and environmental factors contributeto fish survival.

”Being able to identify which habitats are important, not only in terms of which ones are producing fish but which ones are used by fish, allows you to identify which ones are critical,” Brennan said.

Brennan’s research was completed while doing his PhD at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks. It was published in the journal Science Advances.