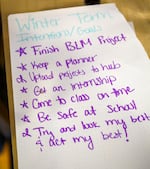

Erica Compare, director of equitable learning, leads a Foundations of Resilience Class at Wayfinding Academy.

Kristyna Wentz-Graff / OPB

It’s the coldest day students and staff members have experienced yet. They’re in class at Wayfinding Academy — a small, private college in the St. Johns neighborhood of North Portland.

About a dozen students sit spread out at desks, wearing masks, in a wide, open room that resembles more of a ballroom than a classroom. Despite the cold, the students stay focused on the task at hand — some with small space heaters atop their desks while others, like 20-year-old Keyanna Kahey, are wrapped in blankets.

Wayfinding has to keep the windows cracked open in the old house it runs classes out of, to limit risk from COVID-19. But the school’s trying some new ways to address long-standing challenges facing people of color seeking college degrees.

On this particularly chilly day, Kahey and her classmates are using paint, tape and a small piece of canvas to create an art project focused on self-identity in a class called Foundations of Resilience.

Kahey is the only Black student in her cohort, and she was the first-ever recipient of the school’s Free Tuition Initiative program — a full-tuition scholarship exclusively for Black and Native American students at Wayfinding.

“I have this honor and this pleasure to be here and to have this opportunity that people don’t have,” Kahey said, “especially people of color.”

Wayfinding Academy began the free tuition program last August, as an extension of the institution’s mission to focus on equity and centering students.

Founder Michelle Jones began planning the creation of Wayfinding Academy in late 2014. She had spent 15 years working in higher education and was disappointed and frustrated with the system, before taking the steps to create Wayfinding.

“It didn’t take too long of starting that career to realize that a lot of what higher education does is actually harmful to students, some students more than others,” Jones said. “It got more and more expensive and it started creating these long-term debt situations for all kinds of people, but also significantly contributing to the racial inequalities related to debt over people’s lifetimes.”

Going against the system

Among Oregon public universities, students of color graduate with more debt, on average, than white students, according to data from Oregon’s Higher Education Coordinating Commission, or HECC.

For example, of students who started at an Oregon public university as freshmen and earned bachelor’s degrees in the 2018-19 academic year — Black students graduated with an average of $29,000 of loan debt and Native American students graduated with an average of $28,000 of such debt. That’s compared to approximately $26,000 for white students, according to the HECC.

“Oregon students of color face enormous barriers and equity gaps accessing postsecondary education, affording postsecondary education and completing postsecondary ed,” HECC’s director Ben Cannon said. “These issues of inclusivity, issues of discrimination and bias, issues of access, are rife within Oregon postsecondary education, and we have a long way to go to make our campuses and cultures more inclusive and equitable.”

According to HECC data, at Oregon public universities, most students of color tend to graduate at lower rates than white students, leaving them at risk of leaving college with debt, but without the higher earnings that often come with degree completion.

Out of full-time students who began at Oregon public universities in 2013, according to HECC data, only 54% of students who identify as Native American earned a bachelor’s degree within six years. The corresponding six-year graduation rate for Black students was about 50% but was significantly higher — about 67% — for white students.

Michelle Jones, president and founder of Wayfinding Academy, Ja. 19, 2021. Jones says after working 15 years in higher education, she realized that for some people of color, attaining an education created a long-term debt situation that contributed to racial inequalities.

Kristyna Wentz-Graff / OPB

Jones said she started Wayfinding looking to upend the “traditional” higher ed system.

She has started small. Wayfinding offers one degree: a two-year associate’s in “self and society” with a focus, Jones said, on helping students figure out what they want to do after college, and how to get there.

Classes have continued in person at Wayfinding even through the pandemic because of the institution’s small enrollment. Currently, just 14 students are attending the school.

Meeting the moment

Jones said Wayfinding turned its goals of racial equity and centering students into tangible action last year by starting the Free Tuition Initiative program.

The program was a move to “meet the moment,” she said. It began a few months after racial justice protests erupted across the country, after George Floyd, a Black man, was killed by Minneapolis police.

“We’ve always wanted to make sure we’re not contributing to the problems that higher education brings with regard to institutions based in white supremacy and that kind of thing,” Jones, who is a white woman, said. “So we’ve always been cognizant of not wanting to add to those problems.”

But Jones said , the college was not necessarily proactively helping to make things better. So, Jones began researching topics like reparations and wealth inequality in communities of color.

Soon after, she pitched the idea of the program to her team. After discussing the legality of the program with the institution’s board, they agreed it aligned with their anti-discrimination policies already in place, and they greenlit the program.

Wayfinding’s director of equitable learning Erica Compere also teaches at the college and was supervising that self-identity art project, as part of a class called Foundations of Resilience.

In her position she said she’s given the institution guidance on how to include multicultural issues in its curriculum, not just for “one class.”

Erica Compare, director of equitable learning, leads a Foundations of Resilience Class at Wayfinding Academy, a small, private college in North Portland, is offering free full-tuition scholarship exclusively for Black and Native American students. The program is an extension of the institutionÕs mission to focus on equity and centering students

Kristyna Wentz-Graff / OPB

“Everybody’s gonna be on the same page and we’re not just going to talk about it for a semester. We’re gonna talk about it all the time because this stuff happens all the time,” said Compere who also works to find mental or emotional support for students who may need it.

She said Wayfinding’s willingness to work quickly towards addressing necessary changes has been refreshing. Like Michelle Jones, Compere also worked in higher education in the past.

“I pointed some things out. They changed the agenda. They had it happen immediately, and I think that’s what’s nice about Wayfinding is it’s small,” Compere said. “Most institutions are these giant slugs, and you have to, like, coax it into action, and then when it happens, it takes a thousand years.”

Compere started in her position at Wayfinding after the Free Tuition Initiative program had already begun, and she said she has a lot of respect for Wayfinding actually taking concrete action.

But, she says, that program is only the beginning of the work.

“The free tuition is to get students here, right? We need to make sure that once they get here, we can keep them here, and it’s very hard going into an all-white place,” Compere said.

Kahey, the Free Tuition Initiative recipient, grew up in Portland and Gresham, so she knew what she was getting into. But, she said, her experiences at Wayfinding have been a stark contrast to the indifference and even explicit racism she had faced growing up and through high school.

She said she felt the difference as soon as she started at Wayfinding.

“I didn’t feel like people were looking at me because I was Black. I felt like people were looking at me because, I don’t know, I was a new person and they were excited to meet me,” Kahey said.

“They were all very open and just wanted to hear about my experiences, not in a degrading way, but ‘I want to know; what is it like?’ Really actually interested, and that was something that was pretty nice to me because I literally grew up in a place where they did not really care at all.”

Kahey took part in the Black Lives Matter protests in Portland, and she said she is proud of her school for taking action to support Black students.

“I feel like when schools hand out scholarships, they just hand out scholarships for the paperwork. They hand out scholarships for the grades. This college handed the scholarship to the person that I am — the color of my skin,” Kahey said.

“I didn’t have to prove myself because I already did, just by being here and being Black and trying like, I already did. And they saw that, and not a lot of schools see things like that, you know, and I think that’s really, really beautiful.”

Equity in higher ed at a higher level

Over the last several years, leaders of Oregon’s largest universities have taken steps to improve support for students of color, but not with the kind of direct support exclusively for students of color that Wayfinding is doing.

In 2015, the Oregon Higher Education Coordinating Commission adopted a new Student Success and Completion Model, which prioritized factors such as how many students are coming from specific marginalized communities.

State funding used to be based solely on how many students they were enrolling.

“For the first time, that year, we started weighting funding based on the race and ethnicity of the students who were enrolling and completing by university,” Cannon, the HECC’s Director, said.

In practice, that could encourage schools to better recruit and retain students of color due to the weighted funding.

“We have made significant adjustments to state financial aid programs, so how we award grants to Oregon students, to try to ensure that we’re driving those dollars toward the students who experience the greatest financial need,” Cannon said. “And that overlaps significantly, although it’s not identical, to our students of color.”

The state agency administers all of its financial aid programs without regard to immigration status, Cannon said.

In 2019, the HECC hired its first Director of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, Rudyane Rivera-Lindstrom.

Rivera-Lindstrom said HECC is aiming to include in its work an understanding of how racial barriers form over time, historically, as well as the unique, recent conditions in Oregon.

“Of course as the disparities have already existed, we know in this past year a lot of things were exasperated because of COVID, because of fires, because of so many things that would definitely perpetuate the existing things that were happening for our students of color,” she said.

Lauren Gross, lead guide, attends a virtual meeting at Wayfinding Academy, a small, private college in North Portland, Jan. 19, 2021. Guides meet with students weekly to help with academic progress, advise students and help counsel them through social and personal challenges.

Kristyna Wentz-Graff / OPB

Although HECC officials pointed out broader efforts to push for racial equity in higher education on the state level, public institutions can’t legally do exactly what Wayfinding is doing.

“There are limitations on the ability of public colleges and universities and the state government, there are limitations on our ability to use race as the determinant in the awarding of grant aid to students,” Cannon said.

“We have explored this issue and continue to explore the question with our legal counsel at the state Department of Justice,” he said. “So, I don’t want to suggest that it would never occur, but it is something that will require some additional work and time before it ever does in the public sphere.”

Private institutions are also reluctant to do something like Wayfinding’s free tuition program.

Linfield University is a private institution with about 2,000 students spread out between campuses in Portland and McMinnville.

The university said it offers very low, and at times free, tuition to many of its students — but, it makes those decisions based on many factors including, but not limited to, race.

This current academic year, 96% of first-year students at Linfield received some form of financial aid, according to the university. Linfield has no plans to do any sort of free tuition program or scholarship based solely on race.

Reed College, a private institution in Portland that has about 1,400 students, said it also would likely not pursue a program like Wayfinding’s.

Reed’s Director of Communications, Kevin Myers, said officials with the school say there seems to be a legal “gray area” as far as offering free tuition or scholarships based solely on race, gender or other characteristics.

Myers said Reed’s priority is meeting the full demonstrated financial need of all admitted students.

Reed does have a “fly-in” program, Myers said, in which the college pays for people of color to visit the college.

“As far as recruiting, there’s been an intention of making Reed’s student body look more like the United States’ population,” Myers said, noting the college has increased campus diversity over the last few years

Jones with Wayfinding still hopes to encourage other Oregon higher education institutions to consider doing something similar to Wayfinding’s Free Tuition Initiative.

“Our annual operating budget is less than half a million dollars a year, so if a tiny college like us with that limited resource has conducted this, then surely every other college in the state that has a lot more money than us and a lot more resources than us can do it too,” Jones said.

Both Compere and Kahey agreed that might be a difficult task to achieve because of Wayfinding’s size, and because of how differently Wayfinding is designed compared to more traditional institutions.

“You have to change the whole system,” Compere said. “It’s a machine. You have to literally unplug the damn thing and get a new computer.”

Working toward expansion

Founder and President Jones wants to eventually open the Free Tuition to all people of color, not only Black and Native American students.

“Our goal is not to stop with just these two identified groups. This is just our starting point. We needed a place to start, and we wanted something we could do immediately,” Jones said. “From a financial perspective, that made sense and that took into account the uniqueness of Oregon’s history and our existing institutional partnerships.”

The institution already had relationships with local organizations in the Black and Native communities, Jones said, so it made sense to start there. Starting small is also giving her time to apply for grants to grow the program, she said.

“With our current scholarship funding, we can afford to do this for about up to a third of every incoming cohort, but to go beyond that, we’re going to need some additional fundraising or some grants,” Jones said.

Support for the Free Tuition Initiative also comes out of paid tuition, other fundraising and program fees and partnerships — such as renting out its North Portland home.

She said Wayfinding has not had to turn down any students who have been eligible for the program.

So far the college has offered the free tuition program to five of its students, including Kahey, and it has not faced any legal challenges doing so yet. A few more eligible students are in the application process, Jones said.

Kahey said Wayfinding hasn’t changed her perspective on what she wants to do after college — something creative, like creative production or even something in the entertainment industry or modeling — but it has increased her confidence in moving toward those goals.

“They make me feel inspired and proud and honored and more than what I am, and it makes me feel like I can do more than what everyone in my high school was trying to say I can. I can be more than just doing hair. I can do more than just playing basketball, volleyball, because I’m tall,” Kahey said. “It’s not even like they opened my eyes. Like, I knew this is what I wanted to do. But they were just like, ‘Yeah, you could do it.’”

Kahey is set to graduate later this year.