Oregon schools are expected to graduate 100 percent of students in the class of 2025.

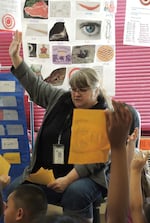

Ms Koblasa passes out pairs of homophone cards.

Michael Clapp / OPB

That doesn’t mean the state plans to make it easier for students to graduate. In fact, schools are raising the bar, aiming to send better-prepared graduates on to college or the job market.

The year 2025 may sound like a long way off. But those future grads are in kindergarten now -- so the standard will apply to them.

OPB is following kindergarteners at Earl Boyles Elementary in East Portland’s David Douglas district. The school is focusing on early education. Today, Rob Manning looks at what it takes to teach kindergarteners “writing.”

Kindergartener Vivianna Lamy is ready for a teacher to look at her writing.

“I want to read my story!”

Her teachers are busy helping other students. So Vivianna reads to me.

Vivianna Lamy

Michael Clapp / OPB

Viviana Lamy: “I like Anna because she is cool and she is sweet.”

Rob Manning: “And who is that a picture of?”

Viviana Lamy: “Anna!”

Vivianna Lamy and Anna Nguyen are in a classroom crowded with kids who should be writing. Some are drawing instead. Others are trying to attract the attention of teachers, or classmates.

Vickie Koblasa has been teaching 23 years -- mostly in kindergarten. She says years ago, young kids weren’t pushed as hard to learn to write and that had an up side.

“They’re getting ideas out there, and their writing isn’t confined to what they are able to put down on paper themselves. So the actual creative part of writing -- they were more creative with their writing, because they weren’t just limited to writing what they can write," Koblasa said.

Koblasa says five and six year-olds come up with long stories. And years ago, she’d let them use scribbles, pictures, random letters and eventually words. Writing, she says, would follow reading.

“And then as they begin to read, they would see how words are traditionally spelled, and so they’d start using traditional spelling, and it just progresses that way naturally," she said.

But Koblasa says that approach produced poor test results in David Douglas.

Oregon used to test student writing at 4th and 7th grades. The legislature dropped those tests in 2011, because they were so expensive to grade, leaving only a high school test.

But in the last year the tests were administered, only about half of 4th or 7th graders passed them.

“When you have kids in kindergarten, and you let them progress naturally, they’re not going to be on track by 4th grade -- it’s going to be a while for them to be on track. And the writing standards are very high.”

Without the tests, David Douglas officials worried student writing could lose ground. So, the district updated standards.

Now it’s joining the state’s adoption of tough national standards known as “the Common Core.”

Students are learning about homophones, words that sound alike but mean different things.

Michael Clapp / OPB

Under the new expectations, kindergarteners should know how to spell 22 simple words -- like “he” and “does.” Phonetic spelling is ok for bigger words. The writing should look right: start with a capital letter, end with a period, going left-to-right, and top-to-bottom.

And one-sentence stories aren’t enough.

“The story has to have a beginning and a middle and an ending. They have to be able to edit, and share it with another person, and read it out loud. There are a lot of standards for writing -- that are huge.”

Koblasa is among the teachers concerned that such rigorous standards can stifle creativity, especially for struggling students.

Now, she's teaching under the new standards. She started in the fall, by having students write their names and simple words.

Words surround students in Ms. Koblasa's kindergarten classroom at Earl Boyles Elementary School (file photo).

Michael Clapp / OPB

By spring, she was leading kindergarteners through short essays.

Koblasa: “You’re going to say either ‘where there’s a zoo, there’s ...'

Kids: “animals.”

Koblasa: “Or, you’re going to say ‘where there’s a school, there’s ...'

Kids: “children.”

Then, the assignment is to take the zoo animal sentence or the school children story, and add adjectives, what Koblasa calls “juicy words.”

When Koblasa asked for kids to read their stories, most kids passed, saying they weren’t ready.

Bryan Castellanos stepped up, though.

“Where there’s a school, there’s children – really nice children, helpful children, clean children, sweet children.”

Koblasa: “Alright – very good!”

That’s a good beginning.

In the “middle” of the story, students describe what the different children are doing, or give examples of different kinds of animals.

The heart of kindergarteners’ learning to write comes from one-on-one teacher-student conferences. Koblasa has 29 students. She does have a student-teacher, Tara Haaga, helping her.

Tara Haaga: “What words do you have written so far – Does this look like Ms. Koblasa’s list up there?”

Student: “Where there’s a zoo -- oh, there’s supposed to be zoo."

Tara Haaga: “That’s right, you haven’t written it yet. Remember, we start at this end, and write that way ...”

Haaga and Koblasa constantly remind the youngsters about writing basics -- the period at the end of the sentence, or putting so-called “finger spaces” between words.

Having one-on-one meetings is a little easier said than done in kindergarten. Students who aren’t in the conferences line up nearby, so they can ask questions when the teacher has a spare moment. At the same time, the teachers try to keep an eye out, so that kids are working, and not goofing off.

When Ms. Koblasa and a student are able to focus -- they can make progress.

Together: “Helpful children help teachers. Sweet children are nice to people.”

Kid: “Uh, the end.”

Koblasa: “(laughs) Nope, can’t get away that easily -- you’re going to have to think of an ending.”

By late May, Earl Boyles kindergarten teachers found their students were a little further behind in writing than in other subjects. About 75 to 80 percent of kids met reading and math benchmarks. For writing, it’s 64 percent.

Vickie Koblasa says grouping kids works for reading and math. But struggling writers need one-on-one time.

“I know they won’t work independently without me sitting there. You saw it today – even turning away and helping the other person, I turn back, they haven’t written anything - until you’re right there, saying ok, next sound, or next letter, or next word.”

Koblasa says her instinct is to help kids having the hardest time – and she notes there’s a focus on the bottom 20 percent. But she says there’s also a real focus on students just below benchmark – more so in the state-tested areas of reading and math, than in writing.

“Because of the testing -- you want the kids to pass the test -- you’ve got to focus on the kids who are ‘right there’ -- and give them the support, and not so much support on the kids that probably, no matter how much support you give them, they’re not going to change the test scores, they’re not going to meet the standard anyway.”

Koblasa also tries to shine the spotlight on students who are succeeding.

Kaylie Smith on left

Michael Clapp / OPB

Her “writers workshop” system has kids read their stories to the class once they’re completely done and edited. Classmates are encouraged to compliment what they like -- the “juicy words,” the handwriting. Kaylie Smith was featured recently.

Kaylie Smith: “I felt pretty – I kind of felt a little shy.”

Rob: “Was it nice to hear the things that they said about it?”

Kaylie Smith: “Yeah.”

The kindergarteners don’t get a break after they finish a story.

As teacher Vickie Koblasa told one student “you never get done during writers’ workshop – you start a new story.”