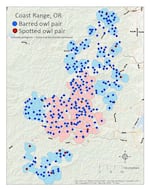

In this illustration of the coast range from Tillamook to Coos Bay, provided by the Oregon office of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, blue dots and red dots represent barred owls and spotted owls, respectively.

courtesy Oregon office of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

When the Northwest Forest Plan was first enacted under the Clinton administration, one of the considerations was protecting enough old growth forest to keep the northern spotted owl species alive. The spotted owl remains a lightning rod and symbol of the conflict between the timber industry and conservationists. In the intervening years, wildlife managers observed barred owls encroaching on spotted owl habitat ranges. Barred owls are aggressive and prolific, edging out threatened spotted owls. One of the only things that will keep spotted owls from going extinct is killing some of their fierce and prolific competitors. Wildlife managers say they’ve seen the evidence of this for years, and now a new OSU-led study confirms it. We talk to the state supervisor for the Oregon office of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Paul Henson about the ethical and practical considerations of reducing one species to save another.

This transcript was created by a computer and edited by a volunteer.

Dave Miller: This is Think Out Loud on OPB. I’m Dave Miller. About 25 years ago, the Northwest Forest Plan reduced logging on old growth forests. A big reason for the plan was to prevent the loss of habitat for the endangered northern spotted owl. But spotted owl populations have continued to plummet, and wildlife biologists have found one big reason why: they’re being crowded out by barred owls. So biologists started killing barred owls to prevent the extinction of spotted owls. Now, a new OS-led study shows that the effort seems to be working. Paul Henson is a state supervisor for the US Fish and Wildlife Service’s Oregon office, and he joins us now with more. It’s good to have you on the show.

Paul Henson: Thanks for having me, Dave.

Miller: Let’s go back a bit. How much did scientists know about the role that barred owls have been playing in the spotted owl’s decline back in 1990 when the spotted owl was listed as threatened?

Henson: Well, we knew that barred owls were out here by that time, although they were a relatively late arrival in the previous century, but we didn’t really understand the impact they were having on spotted owls until the last 10-15 years.

Miller: What made it more clear in the last 10-15 years?

Henson: The precipitous drop in the spotted owl numbers and the abandonment of spotted out territories. And as we were observing for spotted owls, we were also picking up more and more barred owls at the same time, Barred owls were responding to spotted owl calls and surveys, in part because that’s how they chased spotted owls off, by hearing them and finding them and aggressively chasing them away.

Miller: What makes barred owls so successful at a species in the Northwest in particular?

Henson: Certainly compared to the spotted owl, some people refer to them as sort of a super owl, in that they’re more aggressive, they’re bigger. They are a generalist food wise, they can eat almost anything and we can talk about that in a little bit. They’re also very fecund, they produce a fair amount of offspring. And because of their generalist diet they can occupy territories and landscapes at much higher densities than spotted owls who are, in contrast, more of a food specialist and less aggressive and smaller.

Miller: How do their diets differ?

Henson: Spotted owls, as many of your listeners probably recall, are kind of specialists on old growth forest prey species, primarily flying squirrels, other rodents, wood rats, whereas barred owls eat all of that. But they also eat everything from salamanders to crayfish to bats and everything in between. I was just reading a recent paper about some observations of barred owls nesting and feeding bats to their young.

Miller: So one of the things that we have been hearing for years is that spotted owls can really only exist in a particular kind of forest, in old growth forests in the Northwest. But barred owls, it seems they can live almost anywhere. Is that a fair way to put it?

Henson: Well, it’s a fair way to put it. I think on both counts, as we’ve learned more about spotted owls, while they’re still what we refer to as an old forest or a late successional forest obligate species. That is, they really prefer that higher quality older growth forest. Barred owls overlap with them pretty significantly, but barred owls do use a wider variety of habitat. Some folks might remember in Oregon, some reports, for example I have barred owls in my neighborhood here in Portland and they’re in parks, and there’s been reports of barred owls coming down on joggers on jogging trails in Salem, for example. So they are more common and more widespread in their habitat preferences.

Miller: So we have been hearing about barred owls, crowding out northern spotted owls for a number of years now. And we’ve been hearing about efforts to take care of the situation or at least do something by culling some individual barred owls by killing them. What’s the significance of this latest study?

Henson: This latest study, and I do gotta call out the principal investigator of the study. David Wiens, researcher at US Geological Survey. And some of my staff, particularly Robin Bown on the Fish and Wildlife Service staff. But then many other partners at fed, tribal, state and local entities. But the significance of this, about five or six years ago, we really launched a large scale experimental removal project. And we removed about 2500 barred owls from these territories, while we also right next to those territories, those landscapes, we had control areas, what we call control areas, where we just watched the barred owls and spotted owls and documented them. And then did what’s called a before-and-after control experiment. And we saw what happened, and compared: do spotted owls do better, or do they come back, or do they reproduce at higher rates if you remove barred owls? And the results that David and Robin and the team found were quite encouraging in that regard. But it did take several years of study. It takes a lot of effort. A lot of partners. And also, as you can imagine, when you are removing wildlife lethally, you’re killing them. as you described. We had to really go to extraordinary lengths to get stakeholders involved, to make sure that we were looking at all the ethical challenges on doing something like that. And we didn’t do it lightly. And we took our time to make sure we had a lot of stakeholders, including animal rights folks and bird conservation groups involved in the review of this, before we initiated the project.

Miller: I want to dig deeper into the ethical questions in just a bit. But to stick first at the results of this study. So it focused on two sites in Oregon, two in northern California and one in Washington. And in the study areas where barred owls were not killed, spotted owl populations declined about 12% each year. How significant is that decline?

Henson: No, it’s huge. In essence, it guarantees, almost at least certainly from those areas where barred owls are in good numbers, it guarantees that spotted owls will either go extinct or exist at very low numbers and will be a slow path towards extirpation.

Miller: In the places where barred owls were killed, and the paper notes in the method section, that using 12 gauge shotguns, there was a 0.2% annual decline. So, basically steady, but not an increase in populations. So, that doesn’t seem like a recipe for a thriving spotted owl population. It just seems for more of a depleted steady state. What does that number tell you?

Henson: The way one I think should interpret that result is that in five years of study and in some of these sites, cases, a few years of removal is a very short time. I mean, spotted owls live for 20 years. And it’s not surprising to not see, you wouldn’t see an immediate large scale population rebound by spotted owls. It would be, if anything, it should be a slow rebound. But again, it is suggested that it will and just stabilizing the population, as you describe, there’s a significant outcome. And actually, from my perspective, at least having studied these animals for a while, a pretty optimistic outcome.

Miller: But does that suggest then, that lethal control, that killing barred owls, would have to happen in a really concerted way in a variety of places for the foreseeable future?

Henson: It does actually, and it’s a little bit sobering to have to come to that conclusion, but like so much wildlife conservation around the world, and certainly in North America, here in the United States, managing highly invasive species to protect other species, or to protect some of the ecosystem food webs and and things like that, is more and more a part of wildlife conservation. And that issue is being exacerbated even more in the face of climate change and sort of a reshuffling of the kind of species, a species arrangement around the globe and around in these ecosystems.

Miller: How did you, and you noted that before these lethal actions, these were taken in various places, a number of different stakeholders were contacted and their input was sought. How do you think about the ethical questions about killing individuals of one species to potentially save another species entirely?

Henson: Yeah, I can speak not just for myself here, but many of my colleagues in the wildlife conservation field. It’s probably about one of the hardest things, hardest decisions, hardest sort of aspects of the job, and of the career. We all got into this field because we love wildlife, and me in particular, I’m a bird guy and love birds. And there are few categories of birds more exciting and almost spiritual as the raptors. And owls. Within raptors, owls are at the top of that pile as well. So it’s very difficult, but like all ethical dilemmas, it’s usually a trade off of conflicting rights and conflicting values. And in this case, if the decision is having to cull some barred owls every year, as you said, it probably is a long-term and maybe a regular maintenance project, in order to keep another species from going extinct. It’s the lesser of two evils from my perspective. And it’s sort of a Sophie’s Choice, if you will, of what we’re facing. I worked in Hawaii for a number of years, where you’ve probably heard about the extinction crisis going on in Hawaii, primarily driven by invasive species. Likewise, you’ve heard of many other invasive species management cases across the country. And this is now the spotted owl-barred owl issue is now one more issue. I’ll add one more ethical aspect to this that made it a little easier, if you will, to justify this project and this program. This is not spotted owls versus barred owls, it’s barred owls versus everything else, or versus the ecosystem. And as I mentioned, they as a novel predator and a high level trophic in this trophic system . . .

Miller: Does trophic mean . . . ?

Henson: . . . being at the top. They can affect the food web pretty significantly, not just spotted owls, but lots of other critters. So we really need to be aware of that as well. This isn’t just substituting one of owl species for another. It’s barred owls are actually exerting tremendous influence on all the other critters that live in that forest ecosystem.

Miller: I should put a plug in here for a recent conversation, hour-long conversation we had with the Klamath Falls-based writer Emma Marris about three weeks ago, talking in part about the issues just like this. So folks can find that on our website, OPB.org/thinkoutloud. Paul Henson, another wrinkle to me, it seems here, another ethical wrinkle is that, if I understand correctly, that barred owls are in the west to begin with, probably because of humans, because of human changes to the habitat. Does that affect your thinking at all that, that we are now killing these animals to save others, but the ones were killing, they probably wouldn’t be there if it weren’t for us to begin with.

Henson: Yeah, that’s definitely a consideration, and different people in this sort of community, if you will, of conservation and of wildlife, view that somewhat differently to some extent. If it’s, a quote-unquote natural expansion of one species, just sort of colonizing naturally new territory, and moving and impacting other species, some people say, let nature take its course. That’s natural. That’s what the wildlife is supposed to do. From another perspective, this isn’t like someone brought in barred owls on an airplane and drop them off in Seattle or something. Kind of like the situation in the Everglades, would people letting their burmese python snake pets go, and pretty soon they’re now eating everything in the Florida Everglades. But it’s a situation where probably – and I say probably because it’s not, it’s not clear, the science is still a little fuzzy on this – barred owls expanded west from their historic range, probably because of modifications to the the North American forest and plains and prairie environments, caused by human behavior and human activities like farming, tree cutting, just changing of that habitat. And that enabled barred owls to move west across the plains, across the Rockies, get to the far Pacific Northwest and British Columbia. And now they’re working their way down the West Coast and the western mountain ranges and now they’re down into California. And where they’re affecting California spotted owl, which is the subspecies, brethren to the northern spotted owl.

Miller: So given all of this, and in the big picture, what do you see as next for spotted owl management? This is one of the animals that in your position you have focused the most on for so much of your career. Where are they going? And what are we doing to help them?

Henson: Well, believe it or not, after 30 years of doing this, I’m actually still pretty optimistic, and I know that can strike some people as a little odd. But we have a sort of a three-legged stool of spotted owl conservation and recovery. The first one, the first leg of that stool is [to] conserve the best, highest quality habitat, both historic habitat and current habitat with the owl is still hanging on, where the spotted owl, still hanging on.Obviously historic timber harvest, and now wildfires, catastrophic wildfires are some of the biggest threats. So therefore the second leg of that stool would be [to] support active management of some of those forests, where research and the best science suggests we need to rebalance and restore some of those natural processes, to deal with catastrophic fire and forest health issues. And the third leg of that stool is managing the barred owl invasion. And that doesn’t mean going out and wiping out all barred owls across the range, because in fact, that probably [would] be impossible, but it does mean on some subset of the landscape across this range, can you go in every couple of years and knock down the barred owl population and give spotted owls a chance to hang on and do okay. And by the way, we’re doing that in all kinds of other environments for other species in Oregon, and elsewhere throughout North America. So it’s not like it’s new and that this is a raptor and it’s an owl. But it’s not new in terms of the practice of managing wildlife populations in order to keep species from going extinct.

Miller: Paul Henson, thanks very much for joining us today. I appreciate it.

Henson: All right, well thank you Dave. Thanks for having me.

Miller: Paul Hanson is a state supervisor for the Oregon office of the US Fish and Wildlife Service. And I should say that if you want to hear a lot more about spotted owl history, you can listen to all of OPB’s Timber Wars. But you can focus in, if you want to focus on spotted owls, on episode 3 of OPB’s increasingly award-winning podcast Timber Wars.

Contact “Think Out Loud®”

If you’d like to comment on any of the topics in this show, or suggest a topic of your own, please get in touch with us on Facebook or Twitter, send an email to thinkoutloud@opb.org, or you can leave a voicemail for us at 503-293-1983. The call-in phone number during the noon hour is 888-665-5865.