Editor’s note: This article documents the rise of a hate group in Oregon, and includes descriptions of racism, religious bigotry and an anti-immigrant slur.

In January 1921, Ku Klux Klan recruiter Luther Powell stepped off a Southern Pacific train in Medford, Oregon. In the following days, he met with community leaders, including church pastors, police, and members of fraternal organizations.

Powell used these meetings to discover what worried white locals. In Southern Oregon, that meant bootlegging, general lawlessness, and a long-held resentment against Catholics.

KKK Recruiter Luther Powell, 1923.

Wikimedia Commons/University of Washington Digital Collections

Armed with that information, Powell set up a recruitment meeting, where he outlined plans for a new, local Ku Klux Klan chapter that promised to bring law and order to the region. Reportedly, 25 men immediately signed up. In the coming days, he passed out Klan flyers and arranged for lectures. These public events featured speakers who supported the Klan agenda — the roster even included a so-called “escaped nun” sharing her scandalous story of being held captive by the Catholic Church.

Within weeks, Powell successfully formed the state’s first official KKK chapter in Medford. One of its first activities included hooded men delivering a cash donation to a local church. In the coming months, public ceremonies and parades would follow.

The seeds of white nationalism in Oregon had been sown.

Related: A racist history shows why Oregon is still so white

Throughout the early 1920s, Oregon was home to as many as 50 KKK chapters. The exact membership numbers are hard to track down. There are no official records. Historians can only guess based on the few documents and records that remain.

A 1923 Klan newspaper estimated Oregon’s membership at 58,000. Ohio and Indiana were both listed as having about 300,000 members. The same paper totaled the Indiana, Pennsylvania, and Texas membership counts at around 200,000 each. Numbers like these were often exaggerated. Regardless of the official counts, there’s no denying the Klan was once a powerful presence in Oregon and across the country.

Ku Klux Klan members, circ. 1920s

Ball State University University Libraries, Archives & Special Collections

Powell repeated his strategy as he traveled the Pacific Northwest. From California to Alaska, he signed up thousands of new Klan members and established chapters, known as “klaverns.”

He wasn’t alone. Other recruiters, called “kleagles,” opened klaverns throughout Oregon — and across the country. It was all part of a national marketing strategy of the newly incorporated, for-profit business “the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan,” based in Georgia.

Membership was $10. Recruiters kept a portion of that money and sent the rest went back to national leaders. Along with signing up new Klan members, kleagles also appointed additional recruiters. At each level, kleagles kept a cut of all membership dues — effectively creating an organization-wide pyramid scheme. At the time, the average American income was just over $3,000 a year. A motivated Klan recruiter could make that in a few weeks. Powell was motivated.

When the Klan arrived in Oregon in the 1920s, the population was about 97% white, and the state had a long history of racist laws. It was the only state to enter the Union with an exclusion clause in its constitution, which banned both free Blacks and slaves. It also used an anti-immigrant slur, stating no so-called “Chinaman” could own property.

Portland State University Professor Darrell Millner, who has spent his career studying Black history of the Pacific Northwest, said that because there were so few Blacks and people of color in the Northwest, the Klan targeted other marginalized groups that had long faced hostility in the region — new immigrants and Catholics.

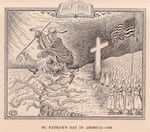

Anti-Catholic KKK cartoon

Library of Congress

“The major target of the Klan in Oregon were Catholics,” Millner said. “And that’s because you couldn’t build a movement against the Black population that was so small and non-threatening in Oregon. But Catholics could be built into a threatening presence here that you could build a movement against.”

Building the movement with dues-paying members was a key objective for the 1920s-era Klan. The national leadership teamed with a marketing firm to appeal to as many white Protestant people as possible. The strategy was to portray the new, revised Klan as a service organization, like the popular fraternal groups of the time. Members staged elaborate public ceremonies, parades, and family events. They held charity drives, partnered with churches, and claimed to support “law and order.”

Ku Klux Klan stages an "America First" parade in Binghamton, New York, circa 1920s.

Bettmann Archive

They also promoted nationalist patriotism and used slogans like ‘One-hundred percent Americanism’ and ‘America for Americans.’ These same slogans have been repeated by groups throughout U.S. history and continue to be used right up to the present day.

“— Darrell Millner, Professor Emeritus, Portland State UniversityThe Klan leaders of the 1920s in Oregon and in other parts of the country were basically using that movement to make money.”

“The Klan leaders of the 1920s in Oregon and in other parts of the country were basically using that movement to make money,” Millner said.

"Catalogue of official robes and banners of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan," circa 1920s.

Prelinger Archives

The organization required members to buy robes and regalia from the official Klan catalog and regularly contribute to Klan causes such as plans for a ten-story office building in downtown Portland.

Klan leadership made millions of dollars while publicly disavowing violence. Yet at the same time, its members were busy stirring up fear and hatred. Members boycotted “undesirable” businesses. They threatened — and sometimes attacked — Blacks, Catholics, immigrants and people they considered “moral degenerates.”

In Southern Oregon, there were at least three cases of so-called “mock lynching.” In separate instances, men were kidnapped by hooded mobs and hung — but not long enough to kill them. The three victims were reportedly white, Black, and of Mexican heritage, and targeted for things like bootlegging and suing a Klan member. These events made national news, prompting Oregon Gov. Ben Olcott to issue a proclamation denouncing the Klan and its violent activities. Across the region, newspapers wrote investigative exposes, and cities banned mask-wearing in public.

Historian Jeff LaLande said growing opposition to the Klan didn’t stop the violence or its political power. “The 1922 election was really the Ku Klux Klan’s opportunity,’” LaLande said, “And it was a successful opportunity to show its political muscle in Oregon.”

“— Jeff LaLande, HistorianThe 1922 election was really the Ku Klux Klan’s opportunity, and it was a successful opportunity, to show its political muscle in Oregon.”

In November 1922, voters elected Klan favorite Walter Pierce as Oregon’s new governor and passed a Klan-supported compulsory school bill. The bill aimed to shut down Catholic academies and other private schools. The U.S. Supreme Court rejected the law before it could take effect. However, other Klan-backed legislation stayed on the books for years, including the Alien Land Act, targeting Japanese farmers from owning land in their own name.

Despite these political victories, the Klan’s power and popularity would only last a few years through the early 1920s. Infighting, corruption, scandal, and growing opposition destroyed Klan support.

As Millner explained, “In any experience where you have tremendous amounts of money and wealth leading to power, you are going to have tremendous turmoil. You’re going to have political infighting and backbiting. You’re going to have all of the kind of political dynamics that we can see flourishing around us in the 21st century now.”

By about 1925, most of Oregon’s chapters dissolved. Though the KKK had held hundreds of events around the state, to date, only a handful of pictures of those activities have emerged. It seemed most former members want to erase the past, forgetting they had ever participated. But Millner said that doesn’t mean the ideology disappeared. “Many people who were active in the klan in the early years of the 1920s will continue to be active in Oregon political and economic and social life deep into the 20th century.”

White supremacist rally at Portland City Hall in Portland, Oregon, 1991.

Oregon Historical Society

“— Walidah Imarisha, Assistant Professor, Portland State UniversityKnowing the state’s history, it’s no surprise that there is white supremacist activity here. Oregon is the home that white supremacists dream of.”

Though the Klan was only active in the state for a few years, it left a lasting legacy. Portland State University Assistant Professor Walidah Imarisha said Oregon still attracts modern racist groups, “Knowing the state’s history, it’s no surprise that there is white supremacist activity here. Oregon is the home that white supremacists dream of.”

Millner tells his students that this is history they need to learn from, but they personally don’t have to feel responsible for it.

“You do have to acknowledge and accept that it did happen,” he said. “And you have to make an individual personal decision, not based on guilt, but based on what kind of future you want to see this country create around these racial issues. That’s the responsibility that you have today.”

Resources and Information

FURTHER READING

Gordon, Linda, “The Second Coming of the KKK: the Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition.” Liveright Publishing, 2017

Horowitz, David A., “Inside the Klavern: The Secret History of a Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s.” Southern Illinois University Press, 1999

Lay, Shawn, “The Invisible Empire in the West: Toward a New Historical Appraisal of the Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s.” University of Illinois Press, 1992

Estep, Kevin and McVeigh, Rory, “The Politics of Losing: Trump, The Klan and the Mainstreaming of Resentment.” Columbia University Press, 2019

Saalfeld, Lawrence J., “Forces of Prejudice in Oregon 1920 – 1925.” Archdiocesan Historical Commission, 1984

INTERVIEWS

Sarah Cantor, Director of Archives, Holy Names Heritage Center

Gwen Carr, Emeritus Board Member, Oregon Black Pioneers

Chuimei Ho, Historian & Author

David A. Horowitz, Professor, Portland State University

Walidah Imarisha, Assistant Professor, Portland State University

Jeff LaLande, Historian

Bettie Luke, Luke Family Association

Darrell Millner, Professor Emeritus and Adjunct, Portland State University

Nicole Yashuhara, Deputy Museum Director, Oregon Historical Society