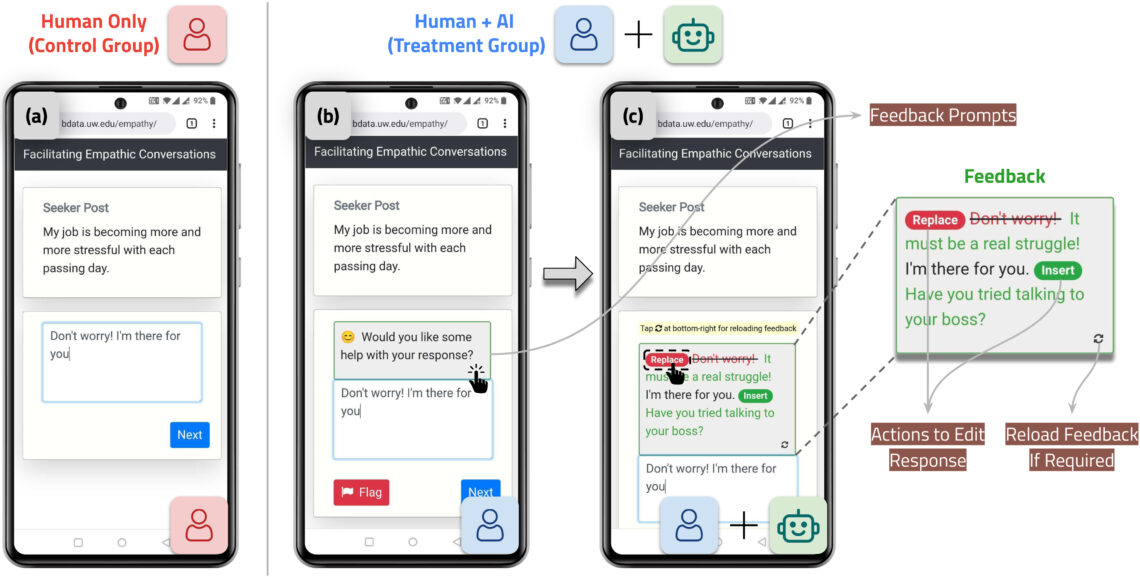

A UW-led team developed an AI system that suggested changes to participants’ responses to make them more empathetic. Shown in this provided figure is an example of an original response from a person (left) and a response that is a collaboration between the person and AI (right). Text labeled in green and red shows the suggestions made by the AI. The person could then choose to edit the suggestions or reload feedback.

Sharma et al. / Nature Machine Intelligence

Peer-to-peer support platforms like TalkLife can help people struggling with their mental health connect to others who have had similar experiences and receive support. While well-intentioned, supporters on these platforms aren’t trained therapists — and researchers at the University of Washington found that their responses to those seeking help often lacked the level of empathy critical to a supportive interaction.

To address this, researchers developed an artificial intelligence system that suggests changes to supporters’ messages to make them more empathetic. They found that almost 70 percent of supporters felt more confident in writing helpful responses after participating in the study.

Tim Althoff, an assistant professor in the University of Washington’s School of Computer Science and Engineering, led the study. He joins us to talk about the nuances of empathy and the challenges of bringing AI into mental health spaces.

This transcript was created by a computer and edited by a volunteer.

Dave Miller: This is Think Out Loud on OPB. I’m Dave Miller. Empathy is a key to conversations about mental health. But even the most empathetic friend or colleague can struggle to find the right words to say to somebody who is in a crisis. For a few years now, a group of researchers at the University of Washington have been looking into a counter intuitive place to try to help these helpers. They created an Artificial Intelligence system to suggest more empathetic responses for peer support providers. And according to the recently published paper, it worked. Tim Althoff is an assistant professor at the University of Washington School of Computer Science and Engineering and he joins me now. It’s good to have you on Think Out Loud.

Tim Althoff: Thank you, Dave. Thank you for having me.

Miller: Why did you and your team decide that this would be a problem that’s ripe for AI to solve?

Althoff: That’s a great question. It all started with studying online peer support communities. Specifically, we worked with a community called TalkLife. It’s a social media platform and an online community where people support each other with mental health concerns. It’s this amazing place where people that are well motivated use their time and energy, their personal experience, even their suffering, to support others in need. So these are amazing people and we really need these communities in order to provide access to mental health care for everybody, which is a huge problem right now.

What we learned, though, on this platform is that people are not trained to be a professional therapist, people are not trained to be a professional counselor and we were thinking about how we can help them learn key skills like empathy. And we had the inkling that AI systems could help train people on these really important skills.

Miller: What are the deficiencies that you saw? And I appreciate that you started by talking about how motivated and willing these people are to help, so this is not a dig at them. But broadly, what did you see as some of the pitfalls or places where they regularly fell short of providing the kind of support that was needed?

Althoff: I should clarify, there’s lots of amazing things that happen on these platforms. But the platforms would be particularly successful, the better the quality is of that mental health support. So I’m a computer scientist, but in this project we collaborated with clinical psychologists and mental health professionals. And when they look at the conversations that people have online, for instance, you would notice a lack of empathy at times. You would notice that somebody shares what they’re going through and sets up an amazing opportunity to empathize with that person first, before jumping to conclusions, before jumping to suggesting alternative actions and recommending what that other person should be doing.

And we studied empathy and how empathy is being expressed. We noticed that many opportunities for empathy were missed when professionals would tell us this is a really good opportunity now to express empathy. We also learned that people, even if they spend a lot of time on these platforms, they don’t learn empathy automatically. They wouldn’t just increase in empathy over time, even though they might potentially be exposed to more empathy over time. If anything people reduced, over time, in the level of empathy expressed.

Miller: We could spend the entire conversation talking about that dispiriting fact. But actually that brings up to me an even bigger question which seems in the realm of science and computer science, which is how do you even measure or quantify empathy to begin with?

Althoff: That’s where this project also started for us several years ago, how to measure empathy. and specifically on these platforms? People exchange text messages in an asynchronous way. So it’s not a face-to-face synchronous conversation. And the way we measured empathy was by trying to not reinvent the wheel. It turns out that clinical psychologists have thought about empathy for decades. Many people have studied how to measure empathy in a face to face conversation with a therapist. And what we did is we took the way people measured empathy in these settings and adapted that to this online world of text-based asynchronous interactions.

So to give one example, one thing that’s not empathic that deducts your points, in a face-to-face conversation, is if I kept interrupting you. That’s not empathic. But I can’t interrupt you when we’re synchronously exchanging text messages. So we took key ingredients that clinical psychologists have studied repeatedly. And that would include things like reacting with what I’m feeling after reading what you’re sharing in your posts, communicating my understanding of your feelings and experiences and trying to improve my understanding of your feelings and experiences typically by asking questions.

Miller: So you set some kind of benchmarks for how to measure the level of empathy in these, as you say, asynchronous text conversations going back and forth in some kind of chat app. So that’s the measurement part. But what you wanted to do was to see if an artificial intelligence could suggest better responses to the helpers. When we’ve had conversations about machine learning artificial intelligence in the past, the way it’s been described is that some huge body of stuff, whether it’s images or texts or whatever, is fed to this algorithm, with some lessons, saying this is what you’re looking for. This is a good example of X. And then if the body of stuff is big enough then the algorithm can actually start to see patterns and recognize what it’s being taught. How did you do that in terms of empathy?

Althoff: Yeah, some of the key ingredients you already brought up. So we had to collect a lot of data on empathy to train these AI systems to help you with empathy expression. The way we wanted to give this feedback, one thing that we wanted to make sure is that, clearly, there’s this really meaningful human-human connection. And I think there’s a risk, with introducing AI systems, that we take away from this meaningful human-human connection. So really we wanted to design the system from the ground up in a way that keeps this human connection at the center. We thought of it as kind of an AI in the loop with backseat human supervision. And whenever the peer supporter wanted, that system could provide feedback similar to how we’ve been getting feedback on spelling, on grammar, maybe in work processing systems for many years now. And the way we trained the system is, as you mentioned, with lots of data.

So we worked with dozens of people that we trained on empathy. They would then annotate lots of messages, with what’s this kind of particularly higher empathy, how exactly was this empathy expressed, which words are expressing empathy, And we collected around 10,000 examples. Then we use these 10,000 examples to look for even more expressions of empathy on this TalkLife platform. I mentioned earlier that there’s many opportunities missed for empathy expression. But the amazing thing with the scale of these platforms today is that it’s still easy to find around a million expressions of empathy. And then we would use these expressions, carefully clean them to make sure we only use high quality data and high quality empathy, in order to train these algorithms. Then that enabled them to give you very concrete feedback on the exact conversation that you’re having right now and help your supporters find the right words to share empathy with somebody which we know is really difficult.

Miller: Can you give us examples here of what an actual peer supporter might have written in their box and then maybe not yet pressed send, and then what the AI suggested saying, ‘hey you might tweak what you’ve written to this before you send it.’ What’s an actual example?

Althoff: Yeah, I can give one and I have to say I learned a lot about empathy myself and I found this really useful.

Miller: Well let’s come back to that, but what’s a real life example?

Althoff: So let’s say somebody shares on this platform, ‘my job is becoming more stressful with each passing day.’ And now the peer supporter is trying to respond. Something we could imagine somebody writing is ‘don’t worry, I’m here for you.’ Now clearly this isn’t the worst thing we’ve read on the internet. But it could be more empathic and specifically this ‘don’t worry,’ I learned, is a red flag if you want to be empathic. Clearly this person is already worrying. So saying, ‘don’t worry’ when they already are can easily come across as invalidating. So in that concrete example that I just said, one thing that AI suggested was it recognized that this, ‘don’t worry,’ might not be a good idea and, for instance, might recommend, you could replace this with ‘it must be a real struggle,’ acknowledging what the person is going through and that it is potentially something to worry about. Another thing that our system suggested in this case was to maybe add something at the end like ‘have you tried talking to your boss?’ And this is added because the AI system noticed that you’re not yet really exploring the feelings and experiences of the other person. You’re not asking them anything, You can probably learn more. And that would be one way to express that in the English language.

Miller: You said that you actually learned more about empathy yourself in the process of doing this research. What have you learned?

Althoff: We chose empathy in the first place because we thought it was such a central skill, not only to these mental health conversations, but empathy can help you in so many human interactions. I’m a computer scientist. I haven’t been formally trained in mental health support. Now we’ve been working in this space for many years and we’re grateful to clinical psychologists at the University of Washington and Stanford University that really helped us understand these really complex and nuanced constructs. And I think, for instance, this ‘don’t worry’ example that I gave, I could imagine I probably said that in situations where maybe I shouldn’t have. I think it’s easy to think you want to help the other person, kind of don’t worry, you don’t want them to worry. But it might not be the most helpful thing to say. And I’ve often been in this situation, maybe supporting family and friends going through something difficult and it’s really hard to find the right words. I’m guessing many people could relate to that. And that’s what the system can help with. The system isn’t, itself, empathic where this computer is somehow good at understanding what you’re going through. It doesn’t, but it can help you find the right words to say in a challenging situation when you really want to be there for a friend.

Miller: That last part is an important point because it’s easy to imagine the jokes about this or the fear that this is somehow some intelligent robot that’s actually feeling human feelings. It’s not. It’s just a tool that has been created by humans to provide a more helpful way for humans to interact with each other. In that sense, it can be easy to lose sight of what we’re actually talking about here. But having said that, after you and the team fed all of this data into the system, did it come up with surprising versions of responses that humans wouldn’t have come up with?

Althoff: We tested the system, working with actual peer supporters of this TalkLife platform and we constructed this large randomized trial where we worked with 300 people. 150 of them would be in what we call the treatment group. They would have access to feedback. They didn’t necessarily need to use it. They could do whatever they wanted to, but they had access, in principle. And then the other 150 would not have access to any feedback and essentially respond like they do today on this platform. And what we saw is that people, even though they didn’t have to use the feedback, actually made quite a bit of use of this feedback. And the resulting responses were significantly higher in the level of empathy that was expressed.

Miller: Did that make a difference to the recipients? Because in the end, what matters most is not a measurable level of empathy in written responses to somebody, but whether it is helping the people who are the recipients of those responses?

Althoff: I appreciate you bringing up this key distinction. So we did measure what was the outcome beyond writing this response? What’s the outcome for the peer supporter, for the helper? They were finding it helpful. They would report often that it’s really challenging to support somebody in need. And one thing that we were excited about is that they reported that after kind of doing the study after receiving this feedback, they would actually feel more confident in helping others in the future. So this was extremely encouraging because what the system is supposed to do is empower people in supporting others. So that was a success.

But what your question also brings up is what was the kind of downstream consequence of this higher empathic message on the original person sharing what they’re struggling with. And this is actually something we intentionally didn’t measure directly through this study. So there’s lots of ethical and safety considerations that we have to navigate when we think about artificial intelligence in the context of mental health. And one thing that we decided with the study not to do is to show this resulting message to the original person in crisis. And we did that because we first wanted to study all the safety implications of using AI systems in this matter and evaluate directly whether we feel that it’s safe. However we know from prior research, not from this experiment, but we could look at observation early and what happens when people are responded to with empathy on these peer support platforms. So this wasn’t active intervention, but just looking across hundreds of thousands of responses, some responding with more empathy than others.

What we did find was that empathy was associated with lots of positive outcomes. So whenever people receive empathy they would be more likely to click ‘like’ or ‘heart’ on this message, they would be more likely to reply to you, and they would also be more likely to follow you on this platform. So we saw the social media equivalent of relationship formation. And that’s not surprising to psychologists at all. That’s something that empathy can do. It can help us invest and create meaningful relationships. And we actually saw this on this platform as well. People were about 70% more likely to start following you and start a longer-term connection when you responded to them with empathy.

Miller: Finally, would you be able, at some point, to study the potential effects of the person seeking support if they knew or didn’t know that the person on the other end was getting help from artificial intelligence? I’m curious if they’re struggling with something and they actually know that perhaps part of the responses they are getting were suggested by a computer, if that would affect the way the help hit them?

Althoff: Yeah that’s a great question and it’s really largely an open question in this field of research. I think we have a strong impression that if the support seeker, as we call them, knew that there wasn’t a human in the loop at all, this might be some AI system responding to them, imagining if that AI system said ‘I understand how you feel.’ Do you? I’m not sure that you do. So how empathy is being expressed, how people express that, chances are this doesn’t work at all coming from a machine alone.

Now your question brings up what if it’s a combination and I think that really brings up important questions here. So we haven’t studied that and that’s a key question for these systems to work. Ideally we want all of these kinds of help to be transparent. And if we receive an email or a letter today and somebody used a computer system to maybe spell check that and check that for grammar, because they care about communicating well to you, I think a few of us would have a problem with that. And it’s interesting to think about what if somebody cared so much about you, that they wanted to use a system that really helps them find the right words because they care about you and they want to make sure that they express empathy. Well, I could also imagine that this works even if the person at the other end knows that they asked for assistance in responding to you in the best way possible. But it is an open question.

Miller: Tim Althoff, it was a pleasure talking to you. Thanks very much.

Althoff: Thanks for having me.

Miller: Tim Althoff is an assistant professor in the University of Washington School of Computer Science and Engineering.

Contact “Think Out Loud®”

If you’d like to comment on any of the topics in this show, or suggest a topic of your own, please get in touch with us on Facebook or Twitter, send an email to thinkoutloud@opb.org, or you can leave a voicemail for us at 503-293-1983. The call-in phone number during the noon hour is 888-665-5865.