A large, carved rock that used to sit near the Willamette River honored an Indigenous creation story that explains the creation of Willamette Falls. Oregon City businessman Frank Busch, pictured here, found the rock and put it on display in the 1930s, but a couple decades later the rock was moved and now it is missing.

Courtesy of Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

A distinctive rock that honors a tribal creation story for Willamette Falls has gone missing.

The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde have been trying to find it because it’s engraved with Meadowlark’s footprints — a series of hatch marks tied to the story of how Meadowlark and Coyote stretched a rope across the river to create Willamette Falls.

In 2019, the Grand Ronde purchased land next to Willamette Falls in Oregon City, reclaiming an area that many of their ancestors were forced to leave in the mid-1800s. Now, the tribes are redeveloping the industrial land at the former Blue Heron Paper Mill and reestablishing their presence at the falls while also creating public access. Other tribes with history at the falls are developing a separate plan to increase access to the falls from the opposite side of the river.

“We used to have a village just a few hundred feet from here,” Grand Ronde tribal member Bobby Mercier said in an interview on the property, known as tumwata village, next to Willamette Falls. “We have stories of how these falls were created in the beginning of time.”

The Indigenous creation story for Willamette Falls is known as an Ikanum; it has been passed down through generations and is only told in the winter. Mercier shared the story as he heard it from his ancestors:

“A long time ago, they were trying to think of a place where they could create a falls to stop the fish, so everybody could eat. And the people there decided that they were going to make this long cedar rope, and it was full of power.

“They gave one side of it to Coyote on that side, and they gave one side to Meadowlark, the little bird, on this side. And they said that they were going to walk. And when both sides decided where they were going to make those falls, they would drop the rope, and it would indent the earth and create the falls.

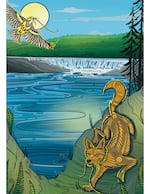

An illustration of the Indigenous creation story for Willamette Falls, which says Meadowlark and Coyote create the falls by stretching a cedar rope across the Willamette River, by Grand Ronde tribal member Steph Littlebird.

Courtesy of Steph Littlebird

“But the thing was: Coyote spoke Chinook and Meadowlark spoke Kalapuya. And they couldn’t communicate to say, ‘Oh, this is a good spot. Let’s drop it here.’ They thought they were telling each other to keep going.

“So they just kept going. They kept walking so far that Meadowlark, his little legs got tired, and he couldn’t keep up with Coyote. And so he just dropped the rope, and Coyote’s like, ‘Oh, this must be the place.’ So he just dropped the rope, and the earth indented and created the falls, and that’s how we got the falls here.”

Grand Ronde tribal members say an ancient commemoration of that creation story used to sit near the falls: a large, flat rock about 3 feet by 4 feet in size that was carved with Meadowlark’s footprints. They say the rock may have been removed and cast aside during the construction of the locks near the falls in the 1870s.

“If we can find the stone, we have a moment to learn from it,” said archaeologist Briece Edwards, director of the historic preservation office for the Grand Ronde Tribes.

Edwards has been working with community members in Oregon City to learn as much as he can about the rock’s history and where it might be now.

“We’ve been able to trace the Meadowlark stone to a place circa 1936,” he said.

At that point, the rock was on display in Oregon City at the base of 12th Street by the Willamette River. A local businessman named Frank Busch had found the rock and put it near the river for all to see. A photo of Busch standing next to the rock still hangs on the wall at his family’s business, Tom Busch Home Furnishings, in Oregon City.

But sometime in the 1950s, Edwards said, the rock was moved.

“The details vary, but we do know that it’s found in historic Oregon City, that it is put on display, that it then is moved to a different location, and that’s where we lose it,” he said.

Greg Archuleta, Grand Ronde tribal member and cultural policy analyst, said the Meadowlark rock is one of many Indigenous artifacts tribes have lost across the region.

“It’s a common story of how objects were … discarded in different ways,” he said. “They could be wood carvings. They could be stone sculptures. … They were pretty significant to these communities, and they were taken away, often sold, and then disappeared.”

Grand Ronde tribal member Jordan Mercier said finding the missing rock with Meadowlark’s footprints is part of a long healing process for the Indigenous people whose ancestors were forced to leave Willamette Falls.

A sketch of Indigenous people fishing at Willamette Falls drawn by Joseph Drayton of the Wilkes Expedition circa 1841.

Courtesy of the Oregon Historical Society Research Library.

“The value of getting the rock back would be the same for any elements of our culture that have been disrupted and the places that are sacred to us that have been damaged or decimated or destroyed,” he said. “Any little thing that can be done to make that right — to right that wrong — is healing for our community.”

Edwards said Indigenous culture is often relegated to a distant past and isn’t thought of as being part of modern life, and finding the Meadowlark rock could help change that.

“How do we take what has been lost or systematically erased through time and find what remains?” he said. “So that the community has that to work with, to anchor to and carry forward in the spirit of keeping it living.”

Edwards said he has a lead on the last known location of the rock, “However, out of respect for the community currently utilizing the space, we have not pursued or pushed into those spaces.”

The Grand Ronde have a different understanding of time and patience, he said.

“There’s a perspective at the tribe: Everything comes home when it’s time. It will be found. Will it be my generation? Maybe. But there’s a certain solace in knowing and accepting that it will find its way.”