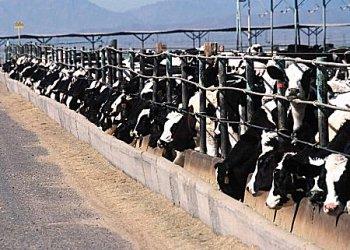

Dairy cows are feeding from a trough on a CAFO, a concentrated animal feeding operation.

U.S. EPA

Hundreds of livestock and poultry operations in the Pacific Northwest are regulated under federal water-protection rules.

Officially, they're called "concentrated animal feeding operations," or CAFOs. Critics have taken to calling them "factory farms."

And when not properly managed, they can contaminate surface and ground water.

One of the challenges with regulating CAFOs is that it's up to the operators to determine if they meet the legal requirements, and apply for a permit, said Ray Jaindl, who heads Oregon's Natural Resource Administration. And without that permit, regulators aren't going to monitor a poultry, dairy, hog or beef operation.

"A guy that has his cattle out all spring and brings them into a corral for winter may not consider that a CAFO," Jaindl said.

Columbia County cattle rancher William Holdner was one of those guys. He was convicted this year on two felony counts of first degree water pollution and 25 misdemeanor counts of second degree water pollution for mismanaging the livestock waste.

"He has been a challenging individual," said Jaindl.

State officials had been trying to get Holdner to apply for a permit since the mid-1990s. They had issued citations and civil penalties. Finally, the Oregon Department of Justice's environmental crimes unit opened and investigation and the attorney general's office prosecuted the case.

As can be seen in the Google Earth photo above, Holdner was storing open piles of manure on cement slab outside his barn, which did not have gutters, Jaindl said. Runoff from the manure piles and from an overflowing storage tank flowed into Mud Creek (the white line on the photograph). A pipe then sent the polluted Mud Creek water into the South Scappoose River.

Holdner was ordered to pay $300,000 in fines and shut down his cattle business within 90 days of his conviction. He did not shut down his operation. More than of his 150 cows were eventually confiscated, Jaindl said.

Although there have been some outliers, Jaindl said, overall, Oregon’s permitted CAFOs do a good job of managing their livestock waste.

To be considered a CAFO, an operation must meet certain criteria.

• Animals must be stabled or confined and fed on a lot or in a facility for 45 days or more during a 12-month period.

• No grass or vegetation is grown in the confinement area.

• A certain number of animals is confined, a number that varies by the kind of animal.

Most CAFOs that discharge wastes to streams, lakes or other water bodies must apply for federal National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits because they are considered point-source polluters. All large CAFOs fall into that category. For instance, a farm or ranch is consider large if it has:

• 700 or more mature dairy cows

• 1,000 cattle other than dairy cows

• 2,500 swine weighing 55 pounds or more

• 500 horses

In the Pacific Northwest, most CAFOs are dairy farms or cattle ranches, but there are others, including hog, chicken, goat, buffalo and horse farms.

What they all have in common are animals that produce manure and urine, and lots of it.

Livestock Daily Manure Production

Note: Feeder stock are raised for slaughter.

Source: Washington Department of Ecology "CAFO General Permit Amended Fact Sheet"

Livestock manure and urine can pollute both ground and surface water with nutrients and organic matter.

The waste contains the nutrients nitrogen and phosphorus, which cause algal blooms that kill fish.

And the waste carries sediments, hormones, antibiotics, ammonia, heavy metals and pathogens. Ammonia is highly toxic to fish and can be converted to nitrates that are poisonous to adults and deadly for infants.

“Parasites from livestock waste can cause disease in humans. Giardia and Cryptosporidia are considered to be the two most important waterborne protozoa carried by livestock, according to the University of Minnesota Extension.”

In the Pacific Northwest, Oregon and Washington agencies are responsible for regulating CAFOs; in Idaho, the U.S. EPA's region 10 office is in charge.

CAFOs with federal NPDES Permits

• Oregon: 113

• Washington: 12

• Idaho: 1*

In both Washington and Oregon, ranchers and farmers are expected to apply for CAFO permits. Those that discharge waste to waterways apply for the federal pollution discharge permit; smaller operations may qualify for a general CAFO permit.

Washington is streamlining its CAFO permit system, said Nora Mena, a manager in the Department of Agriculture. About 100 dairies had permits until 2006, when many permits expired and other were terminated because they no longer discharged wastes, she said.

In Idaho, 100 CAFOs had NPDES permits, but those permits expired earlier this year. To date only 1 CAFO operator has applied for a new permit, said Nicholas Peak, with the U.S. EPA, which handles NPDES permits in Idaho.

In addition to managing 113 federal pollution discharge permits, Oregon's Department of Agriculture has issued 419 general CAFO permits to smaller farm and ranch operators, Jaindl said.