Outside Bend City Hall.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra / OPB

Unlike every other large city in Oregon, residents in Bend don’t get to elect their mayor.

Instead, Bend’s seven city councilors — who are elected at-large — appoint the mayor themselves.

In Bend, being mayor is also a part-time job with just a two-year term. That’s because Bend has what’s known as a weak mayor system. That means the mayor and city councilors basically have the same amount of power.

Former Bend Mayor Jim Clinton referred to this form of city government as a “small town concept” — one built for a place that doesn’t have to think about issues like traffic, affordable housing development and expanding urban growth boundaries.

But Bend's not a small town — not anymore, at least. Voters in Bend have a chance to amend the city charter in May to make it so that residents get to decide who their mayor will be. Measure 9-118 would also allow the mayor to serve a four-year term instead of just two years. City councilors voted in favor of putting the issue to voters in December. During that meeting, councilors rejected the idea of a ward system for electing city leaders.

“It’s kind of putting [on] the big boy britches at some point,” said Chad Sage, chair of the Century West Neighborhood Association who sat on the city’s Charter Review Committee.

More than 91,000 people live in Bend now. Researchers predict that by 2030, that number will look more like 130,000.

Related: Growth Prompts Speed Limit Changes In Key Areas Of Bend

“That’s really significant for a city that’s really really wrapping its head around urban growth issues, land use issues, traffic — issues that every city looks at certainly, but they seem to come to Bend in spades,” Sage said.

Bend is now the fastest growing big city on the West Coast, according to the latest census data. It's also the largest city in the state of Oregon where citizens can't elect their own mayor.

“The closer people are to their elected officials and into how their government works, the better that representation will be, and the better that government will work for them,” said Nathan Boddie, a current city councilor who’s running to be a state representative.

The question about what an appropriate form of government looks like for Bend is wrapped up in a larger question about how one of the fastest growing cities in America responds — and adjusts — to its rapid growth.

The east-west divide, and the fear of getting left behind

Brent Landels calls Third Street the “dividing line” between east and west Bend.

He chaired Bend’s Charter Review Committee and works in an industry often tapped as a litmus test for a city’s growth: real estate.

Landels, who used to be heavily involved in his local neighborhood association in east Bend, says there's a feeling that the east side isn’t developing as quickly as the west.

“It just feels a lot different [on the east],” Landels said as he drove over a bypass. “Talking to people on the east, they definitely have the opinion that money gets spent on the west side first.”

Landels thinks this has everything to do with Bend’s current form of city government. Landels points to at least two instances of this idea that, historically, most of the people with influence in city government come from one side of town: the west side. The idea of electing a mayor at large, he says, could get the city's leaders to think citywide.

For example, currently, just two of Bend's seven city councilors are from the east side of town. City councilors are in charge of appointing people to committees that take up important issues. One committee was in charge of making recommendations for the city's urban growth boundary.

Of the 45 people appointed to the most recent urban growth boundary committee, 41 of them came from the city’s west side.

“It becomes an echo chamber,” Landels said. “Because of the way the council is formed and how many people are on the council and where they live, in my opinion, then the committee appointments become heavily towards [who you know].”

One possible explanation for that imbalance is participation. According to a community profile of Bend put together by the city's Metropolitan Planning Organization, most households with incomes at or below the federal poverty line are on the east side of town. People with money may have more time and resources to participate in local politics.

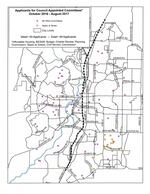

An analysis of applications for council-appointed committees found more people from the east side of Bend applied to be on committees than people from the west side.

City of Bend

An analysis of applicants who apply for an appointment to a council-appointed committee refutes that claim; between October 2016 and August 2017, 49 people who applied to join a committee were from the east side, compared to just 45 on the west.

West Bend, meanwhile, continues to be the site of large projects. That includes the growing Oregon State University-Cascades campus.

The hope that comes with a mayor elected at-large

Boddie, a current city councilor who works as a physician in east Bend, doesn’t deny that economic disparities exist in the growing city. He says they’re an artifact of how Bend grew. A lot of the east side is newer, compared with older, more established areas of west Bend.

“It’s not because anyone has designs on council to create or worsen that inequality,” Boddie said. “You can see the disparities, you can feel it, and its real and you can put it down on a piece of paper the average incomes and the housing cost and it’s true. It’s a problem and we need to fix that problem.”

Boddie says perpetuating the idea of Bend as a bifurcated city is divisive. He also says it’s created space for the idea of letting citizens decide who will lead and unite the city.

“We have to look beyond just our neighborhood,” he said. “We have to think of ourselves as Bend and Central Oregon and how do we make sure the way we grow isn’t ruined by some future version of ourselves?”