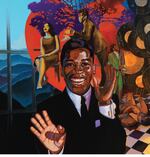

Portland artist Isaka Shamsa-Din has an exhibit at the Portland Art Museum.

Isaka Shamsud-Din

Portland artist and activist Isaka Shamsud-Din has captured the lives and histories of African Americans in paintings throughout his life. He draws on his experiences growing up in Portland for his work. His exhibit, “Rock of Ages,” is currently on display at the Portland Art Museum. We spoke to him in January 2020.

As reported earlier by Oregon ArtsWatch, Portland artist, educator and activist Isaka Shamsud-Din has died. The arts and education nonprofit Don’t Shoot Portland announced earlier this month that the artist had entered hospice care. Shamsud-din had been ill with cancer for some time.

We listen back to a conversation we first aired in January 2020 with Shamsud-Din when his exhibit, “Rock of Ages,” was on display at the Portland Art Museum.

Note: The following transcript was transcribed digitally and validated for accuracy, readability and formatting by an OPB volunteer.

Jenn Chávez: From the Gert Boyle Studio, this is Think Out Loud. I’m Jenn Chávez. We end today’s show by remembering Portland artist, educator and activist Isaka Shamsud-Din. According to the arts and education nonprofit Don’t Shoot Portland, Shamsud-Din entered hospice earlier this month. Oregon ArtsWatch announced his death after a long illness with cancer last week.

Think Out Loud host Dave Miller spoke with him in January 2020, when a solo exhibit of his paintings was on display at the Portland Art Museum. The artist started the conversation by talking about his father, who was featured in a large portrait as part of the exhibit.

[Recording from 2020 interview]

Isaka Shamsud-Din: Well, he was a farmer at heart. He was a magician with the soil and he even hybridized some certain plants. He was just an extremely industrious man. He worked all the time and he had a joy of living that you could really see when he was working with the soils. So we had a garden everywhere we went, even when we lived in the projects he managed to get someone who had private property to allow him to use part of it to grow a garden. He recognized my being an artist earlier than just about anyone outside of people at school, students and teachers, and was my biggest and first real supporter.

Dave Miller: What did you learn from him, do you think?

Shamsud-Din: Well, I learned so many things from him. I guess being steadfast, and being able to overcome tremendous hurdles and challenges without whining and without casting the situation on to anyone else. And his positive temperament at all times.

Miller: You put a small rectangular mirror embedded in the canvas of that painting. It’s basically at eye level with your father, so when we viewers look at this painting, if we’re tall enough – and you’re pretty tall – we could see ourselves in the painting. What was your idea of embedding that mirror, an actual mirror, in the work?

Shamsud-Din: Well, I’d like to say something heavy. But my work is purposefully not fully constructed before I go into a piece. So I always leave myself open to an idea or a color to go in a particular place, or movement. Something to engage the viewer in a way that is unexpected. This time it was just a notion toward the end of the painting. And I didn’t want to take it any further than that, at least it didn’t occur to me to take it any further than, as you stated, you’re looking at him, but you’re looking at yourself too.

Miller: That portrait, and a number of others in this exhibit, feature hands that are way bigger than than hands are in real life, powerful hands that really catch our attention. His hands are low down sort of in front of his chest, but they just stick right out of the painting. And there are other portraits where the same thing is true. Why make hands so big?

Shamsud-Din: Because they’re so important. And again, some of my work comes through not consciously. In other words, I wasn’t thinking. I didn’t pre-think that to say, “let me make these hands that much bigger.” I think unconsciously it’s because of the work of the hands. The hands are so important.

When we were in Texas, we didn’t have electricity, we didn’t have running water inside. Daddy was still plowing with mules and horses. And that was in 1947, so he had mastered that kind of life. We produced prodigious crops every year. We’re tenant farmers. So we trusted, in my way of speaking now over 70 years since that time, a confidence that comes from mastery of the task at hand. To know what you have to know to run a farm with no electricity and those other amenities or necessities to most people, you had to know a lot. You had to know a lot to be able to keep your animals healthy, to be able to handle all the harnessing, for instance.

There was a lot of craft, a lot of knowledge. We felled our own timber, we made our own syrup, we made soap, we made candles and so forth. We just did those things with ease because we knew what we were doing. My father and my mother.

Miller: Why did your family leave Texas?

Shamsud-Din: Well, on one night – and of course we were in the backwoods also, so a Greyhound bus was like a little ant, it was that far away from where our house was – Daddy told us to all hide, and put out the lamps, candles and so forth. We were hiding under the beds in the middle of the night, early in the evening at least, very dark. Some people came and got him. And it wasn’t until the time of that painting that I did from a photograph I did of him in front of his garden in San Bernardino, it was nothing more … It was a big thing to me because it kept reappearing, that scene, that event. Although I didn’t know if it really happened or was it a dream. Even though I was 7 years old, things weren’t explained.

Miller: What did you end up finding out from him or others about what happened that night?

Shamsud-Din: Well, I asked him directly. And he said a group of white men came and took him away. They call themselves a mob crew. They went to collect other men to help them and they took him out to a place. He was left for dead, tied to a tree at this place called Bowie Hill. Some six months later, he was able to bring us all to Portland.

He’d never been to Oregon before. He moved to Vanport. And of course, just to disperse of all of our belongings that we didn’t need anymore – the wagons, the mules, horses, cows, chickens and all of that – that was left up to my mother, older brothers and sisters. It was amazing what they were able to do.

Miller: You ended up in Vanport in 1947. Then, as I hope at this point most of our listeners know, there was the terrible Vanport flood on Memorial Day of 1948. How old were you?

Shamsud-Din: I was 7 then.

Miller: What do you remember about that day?

Shamsud-Din: Well, I remember that my mother was preparing food, it’s Memorial Day. And about midday, a note was shoved under the door. And I understand that it was shoved under other people’s doors. I actually had a copy of it, I can’t find it now, but it said “do not panic.” Essentially, we’ll tell you when to evacuate.

Miller: And this was from the authorities: “The levees are fine, don’t worry.”

Shamsud-Din: They didn’t go into any more detail than that, but that was what that meant. Not that they were fine, but we will tell you when to evacuate. Everyone knew that they were ready to overflow. As a matter of fact, I found out years later, when I was working at Portland State doing work study in the library looking at the bound volumes of the old Vanguards, that they had evacuated Portland State, which at that time was Vanport Extension Center. They had already evacuated that, taken the books, desks and all that stuff a couple of weeks before we got that notice.

Before an hour or so, we could see a man was running down the street hauling, “the dike has broke,” and we could see water coming right behind him. My family was in the first group of apartments, right on Denver Avenue coming out of Kenton. So we were able to make it to the top of the banks before most other people did.

Miller: So by the time you were 7, you essentially either been chased off or flooded out of the two homes you had known. How do you think that’s affected your life going forward, those early formative experiences?

Shamsud-Din: Well, they set me with a certain tone. Of course we didn’t know why. No one ever spoke about when they came to take my father away. No one in the family. That’s why I had to ask him.

Miller: Thirty years later.

Shamsud-Din: Yeah. But Portland was very unfriendly and was unwelcoming to Black folks in the main. And then when the cops started attacking my two older brothers, harassing them in Vanport, it was just an attitude, that I knew that we were among people who … I didn’t know [why] we left Texas, remember. We were very aware that we were not wanted here. And it’s just set a more combative kind of attitude, I think. I never diagnosed this or analyzed this before.

Miller: How many representations of African Americans or Africans did you see in artwork when you were growing up?

Shamsud-Din: Actually, I saw none. My first formal experiences I’m thankful for because I learned a lot of things from Manuel Izquierdo at the Museum Art School Saturday children’s classes when I was 13. But no African, African American or African diaspora artists were presented to us. I was the only Black student and that was my situation a lot of my schooling. So it was the earliest influences, is that what you’re getting at?

Miller: I was curious about that, and I was curious if and how that did influence you, that you didn’t necessarily see yourself reflected in work you were studying or work you’re exposed to?

Shamsud-Din: Yeah, but at that time, of course it was consistent along with everything else. My family was a churchgoing family. And it really bothered me, I remember, from the very earliest, these white Jesuses, the white Marys, the white Josephs and so forth. I felt alienated. These are things that I kept to myself, but inside they were tearing me up. The why, where am I, where are we? That’s what I was really thinking.

And of course in school, there were no Black folks that were held up. I don’t think I learned anything about Frederick Douglass or any of the other people that people know about now. And it was hard for me to stay in school for that reason. So I just started reading Black novels on my own – Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, “Invisible Man” and so forth. When I started digging on my own to learn about African American artists, it was Charles White. There were very few periodicals or any art media that featured Black artists.

Miller: I want to turn to another painting in the show at the art museum right now. It’s a long wooden panel, it’s super vibrant, it’s almost electric. It’s an interior of a bar that you write, in the little explanatory panel, was near your studio. And you write there that you used to go to that bar to sketch. What attracted you to that place? Why’d you go there to draw or or sketch?

Shamsud-Din: My apology, but I didn’t actually go there to sketch. My studio was next door. I’ve always been attracted, once I decided to try to tell stories about African people’s lives in America, those that I knew, the people that I saw all the time resonated of course more than any other to me. So when I would take a break from my studio, which was next door … this place was called Welcome Inn on Alberta Street. I used to have my sketch pad with me everywhere I went anyway, even if I was in court. Wherever I was, I always had a sketch pad. And I hadn’t planned the painting. I was just sketching.

Miller: As I mentioned, we can see your paintings in the museum now. But people, if they’re going to PCC, the Oregon Convention Center or driving around, we can see your murals inside and outside Portland as well. Making murals seems like it has been a really significant part of your professional life, your art making life. Why have you made that choice to put such an emphasis on these very public works?

Shamsud-Din: I started making murals in ‘64, when I was a student at Portland State and the art department had decided to grant commissions – they weren’t much money – to upper level students to paint murals. And none of the murals were figurative. I saw some other guys, some other art students, people I knew, painting murals in the cafeteria. And I thought that was a poor place, because they were low, right next to the tables and so forth. So I drew up a proposal to do a mural that was much bigger. I finished that in ‘65.

But I really didn’t and still don’t see myself as a muralist. I do all kinds of things. I’m always making stuff. I can’t help myself. The idea for murals was to make not only myself but other African American artists visible. At that time, in ‘77, I think I might be the only African American artist that had gotten a commission from the Regional Arts and Culture Council, at that time called the Metropolitan Arts Commission. So it was to make us visible, to tell stories and to illuminate something of the Black experience. And as a signature of pride and color, adventure that everyone could see. The exhibitions, galleries and so forth, it’s just a limited number of people that will ever see those. So I’ve done a lot of printmaking. I’ve done a lot of carving. I’ve got a couple of wood carvings at my studio right now. I’ve worked in stone. And I’ve cast concrete pieces that are at Dawson Park right now, they’re airbrushed historical pieces.

Miller: We’ve talked about some of the trauma you’ve experienced in your life, some of the loss. You don’t shy away from that in your work, but there’s also so much joy in a lot of your work. How do you think about that balance between pain and joy in the work you’re putting out in the world?

Shamsud-Din: Well, to tell history is so important to me. I really owe a lot to the history writers, the photographers that I draw from. But I wanna talk about triumph and amazing people, and also the struggle, and what kind of obstacles and problems that they had to deal with, a lot of it based on our society and the way the society is unevenly structured.

Miller: Isaka Shamsud-Din, thanks very much for coming in.

Shamsud-Din: You’re very welcome.

[Recording from 2020 interview ends]

Chávez: That was Isaka Shamsud-Din, speaking with Think Out Loud host Dave Miller in January 2020. The Portland artist recently died after a long illness with cancer.

Contact “Think Out Loud®”

If you’d like to comment on any of the topics in this show, or suggest a topic of your own, please get in touch with us on Facebook or Twitter, send an email to thinkoutloud@opb.org, or you can leave a voicemail for us at 503-293-1983. The call-in phone number during the noon hour is 888-665-5865.