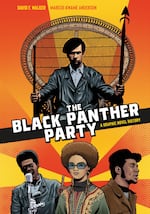

The opening page of The Black Panther Party: A Graphic Novel History depicts party leaders Huey P. Newton, Bobby Seale and Kathleen Cleaver.

Marcus Kwame Anderson

The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense was formed in 1966 in Oakland, Calif., by two friends and fellow college students, Huey P. Newton & Bobby Seale. The history of what became one of the most famous and revolutionary organizations of the Black liberation movement is told in illustrated form in the new book “The Black Panther Party: A Graphic Novel History.”

As its introduction reads, “the Panthers defiantly stood in stark contrast to the nonviolent philosophy of the mainstream civil rights movement. … Some people admired them. Some people hated them. In time, the Black Panthers became mythical — and it can be difficult to separate myth from reality.”

The book, a vibrant collaboration between Portland-based writer and historian David F. Walker and illustrator Marcus Kwame Anderson, seeks to make that separation.

The cover of The Black Panther Party: A Graphic Novel History, by David F. Walker and Marcus Kwame Anderson.

Marcus Kwame Anderson

In tracing the historical context for the Black Panther Party’s political philosophy of self-defense, the graphic novel starts with the oppression of enslaved Africans in the United States, follows the enduring racist violence & police brutality of the Jim Crow era, along with the emergence of Black Nationalism and famous events in the nonviolent civil rights movement led by Martin Luther King Jr. and taught in many American schools.

In doing so, Walker and Anderson trace the ideological origins of the Black Panthers, drawn in part from the philosophies of figures like Frantz Fanon, Malcolm X, Karl Marx and Che Guevara. It pinpoints a speech by activist Kwame Ture (then Stokely Carmichael) at a nearby conference about Black Power and its goal of self-determination for Black people as part of the young Newton and Seale’s inspiration to form the group in October 1966. They appointed themselves Minister of Defense and Chairman, respectively, and created the organization’s Ten Point Program, which called for “land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace” for Black people. The new organization staunchly opposed and confronted the police brutality it saw routinely deployed against Black residents around the San Francisco Bay Area.

Throughout the book, Walker and Anderson illustrate the complexities of the Black Panther Party from its rise in 1966 to its fall in the 1980s, dramatically hastened by suppression and interference of the federal government’s then-secret COINTELPRO programs. It puts into action better-known episodes of the party’s history, like its armed protest at the Capitol building in Sacramento. Other examples include the “Free Huey” campaign to release Newton from prison after he was charged with attempted murder — charges that were eventually dropped, freeing Newton in 1970 — and the police killing of the party’s Illinois chairman, Fred Hampton, during a raid in Chicago.

Portland writer and historian David F. Walker.

Ten Speed Press

The book also examines the party’s deep-rooted community work, such as its free breakfast programs for schoolchildren across the country. It celebrates prominent women in the party’s history, like Angela Davis, Kathleen Cleaver, Elaine Brown (the only woman ever to serve as Chairman of the national party), and Ericka Huggins. At the same time, it spotlights lesser-known party figures, and the day-to-day work of the party’s many rank-and-file members, often left anonymous in conventional histories of the Black Panther Party.

Portland’s David. F Walker writes in the book’s afterword that, due to many similarities he uncovered in his research with modern conditions that served as a catalyst for the Black Lives Matter movement, “writing this book broke my heart.” He recently talked with OPB about the book, the Black Panther Party, and its influence and legacy today.

Jenn Chávez: Your book starts with centuries of historical context for how the Black Panther Party’s political philosophies formed. One detail I personally found fascinating was how Lowndes County, Alabama, helped set the stage for the Black Panther Party. That’s where activists like Kwame Ture, then Stokely Carmichael, began to evolve a little bit in their strategy of nonviolence. How did the Black Panther Party mark an evolution of the movement ideas and strategies that preceded it?

A panel in the opening pages of The Black Panther Party: An Graphic Novel History describes the party as "a complex organization that had an equally complex relationship with the communities it was dedicated to serving."

Marcus Kwame Anderson and David F. Walker

David F. Walker: Really, we’re talking about a time in the sixties during the civil rights movement where the main focus was on nonviolence and the idea of turning the other cheek. This was really central around Dr. Martin Luther King, and the Southern Christian Leadership Coalition and SNCC [the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee], and Stokely Carmichael was part of SNCC. They were younger people and they were having a lot of trouble really getting down with this idea of nonviolence, especially because a lot of the places they found themselves in, they were meeting with a lot of very violent resistance.

And out of these younger Black activists came this philosophy of, I guess for lack of a better term, you could call it self defense. Malcolm X had talked about this quite a bit when he was in the Nation of Islam, and then even talked about it more after he left the Nation of Islam. And this idea of Black Power just sort of began to emerge, and the Black Panther Party was really the culmination of that Black Power movement in some ways. But in Lowndes County, as [members of SNCC] were trying to register Black voters, they were meeting with so much violence that the people there felt there was only one way to resist, and that was to stand up and fight back.

Chávez: Your collaborator on this book was illustrator Marcus Kwame Anderson, and he not only gives these shots of energy to scenes and events, but he also fills the book with beautiful portraiture, including of party leaders and lesser-known party figures. One really stunning section that I remember is portraits of dozens of civil rights activists who were murdered for their activism. What do you feel his work as an artist communicates that wouldn’t have gotten across with just writing alone?

Walker: Absolutely everything. I mean, I’m such a strong proponent of this medium, and I happen to believe that reading as a practice, as an art form, is never better than when there are images to go with it. That goes back to being four and five years old when I learned how to read. Marcus is such an amazing artist. He’s someone I wanted to work with for a long time, and I was familiar with his work, so I knew that he had a very diverse style. Part of the reason I wanted to do this was because I feel like, especially with young people, there’s a lot of young people who have trouble engaging with reading, especially when it’s dense, heavy material. And there’s no reason for that. There is a way to engage people and to activate some of their other senses. I couldn’t imagine at this point in my life or career, writing a book like this one and not having to be heavily illustrated.

Chávez: The history of the party has its famous figures: Huey Newton, Bobby Seale, Fred Hampton. But you have dedicated this book to the rank and file of the party, who you write were “its heart and soul.” Can you talk a little bit more about the day-to-day community work they did for the party?

Walker: The rank and file of the Black Panther Party — there were chapters all over the country — there were actually chapters all over the globe. Pretty much any city that had a branch or a chapter of the party, they had a free breakfast program for kids. There were health clinics in some cities. There were programs that helped people who had family members who were incarcerated, helped them get to the prisons for visitation. And, of course, there was the newspaper, which came out weekly, and was produced in the Bay Area and then shipped all over the country and distributed every week.

All of that was part of the day-to-day operation of the Panthers, especially the rank and file members. Getting up before the crack of dawn to prepare these meals for kids, serve those meals. When the paper came out, distributing it, selling it. And then, actively engaging within the community. When you think about the Panthers as a whole, there’s maybe a dozen at the most who we know. But of those dozen people — that’s not enough to make an organization run and to have this sort of impact that the Black Panthers had — and so, really, it was the rank and file.

Chávez: One of the party’s most famous acts at the time was its protest in Sacramento. Members went to the state Capitol armed, to protest a gun control proposal that was essentially designed to disarm the Black Panther Party, which would have made it illegal to carry loaded guns in public. I’m wondering how you think we can look back on this, in contrast with today, where the gun rights movement looks very different, and where we’ve seen actions at capitals by far-right extremists.

A panel of The Black Panther Party: An Illustrated History features Bobby Seale reading the party's Executive Mandate #1 at the site of the party's Capitol protest in 1967.

Marcus Kwame Anderson and David F. Walker

Walker: On January 6th of this year, when we saw the insurrection in Washington, D.C., one of the first things I thought to myself was: when the Panthers showed up to the Capitol in Sacramento in 1967, they had their guns, but nobody got hurt, nobody got killed, and every single member of the Panthers wound up being arrested. And there were people who were arrested at the scene who weren’t even in the Panthers, they just happened to be innocent bystanders.

As a result of that, also, the strictest gun control laws at the time were enacted in the state of California, with the express purpose of disarming the Panthers. What we see today, especially in the aftermath of January 6th, is the absolute hypocrisy of not just ‘law and order,’ but the hypocrisy of, say, gun rights activists. The same people that are screaming about, you know, ‘don’t take my guns away’ were also the same people that were working to take away the guns of the Panthers.

The interesting thing I like to point out is that the vast majority of the things that the Panthers did — I’m not gonna say they didn’t break any laws along the way, because they did — but the vast majority of the things that they set out to do were within the scope of the law. And a lot of the times, the things that they did that were considered ‘illegal’ [were] illegal because the laws were changed to make it illegal. In order to defeat them, ‘law and order’ either changed its rules or broke the law itself.

Chávez: You’ve written that your views on the Black Panthers became more nuanced and sometimes more complicated, in learning so much that you previously did not know about them. Can you tell me what surprised you or complicated your views?

Walker: There are a couple things. One was the age of the members of the Panthers. I always knew that they were young, and when I first really started studying the Panthers, I was about the same age that most of them were, which was late teens and into their early twenties. But as I was writing the book as a middle-aged man, somehow it really clicked that I was writing about people that were, at this point in my life, old enough to be my children. And so there was that aspect of it.

But there was also, there are certain people within the party who, certain ideologies or things that they did, I didn’t agree with. And then, as I studied more about some of these individuals, I really came to dislike them. And it’s not the best thing to cast moral judgment on someone that you’ve never met. But there was at least one particular individual in the party that I ended up not liking so much through my research, the things they said and did, that I really had almost a moral dilemma about including them in the book. But at the end of the day, I realized that this book that I was writing was not meant to be an extension of my own morality. It was meant to be a historical document.

Chávez: You wrote your epilogue to this book on May 27th, [2020]. And that was just days after police killed George Floyd. And in the months since, Portland became one epicenter of the racial justice uprisings across the country. Notably in attendance at some protests was the founder of the Portland branch of the Black Panther Party, Kent Ford. With the months that have passed since, how do you see the history you wrote about — the movement and what it fought against and how it was suppressed — still present today?

Walker: Well, you know, there’s that old saying that history repeats itself. After the killing of George Floyd and the subsequent uprisings, within those first couple days especially, if there was one person in this country who wasn’t surprised in any capacity by what was happening, it was me. A lot of that was because I was coming fresh off of writing this book.

What I can say is there are aspects of this country that have gotten better, or at least they have changed considerably. I mean, when we look at who our vice president is right now, that’s a sign of change, but that isn’t necessarily a sign that things are better. And what I find most disheartening and troubling is that, within the Panthers’ Ten Point Program, every single thing that they talked about wanting and needing is still relevant today, 55 years later.

The other thing that I find equally troubling and disturbing is that. at the time that the Panthers formed, the U. S. Government commissioned a special research project, that the end result was the Kerner Commission Report, that literally predicted everything that happened last summer. In terms of the violence and the uprising, but it also predicted the disparity in wealth and racial injustice that this country was going through and was going to continue to go through. And the thing that just sickened me and continues to sicken me to this day is that, as a country, we’ve known and we’ve been willfully ignorant to the fact that where we are today is where we’ve been headed, not just since 1967, 1968, but where we’ve been headed since the day that the Constitution was written and they were arguing over what to do about slavery.

So many of the things that this country is facing, so many of the problems, so many things that make the United States not an equal nation, and the land of injustice, every single one of those things has been around since the beginning, since the founding of this country. And every time we talk about it and say, what can we do about it? We do nothing. And we just saw this happen in the aftermath of the January 6th insurrections and in the acquittal of Donald Trump. And none of it surprised me, again. I hate to say that, but it was like, the only tension that I had watching the impeachment hearings was, how long is it gonna take for them to acquit him? Not, are they going to? Because I knew they would. Because in order to find him guilty, it means having to find this nation guilty of the things that it’s been doing for a long, long time.

Chávez: Do you view this book as part of the Movement for Black Lives? And if so, what do you feel your role is in that movement, as a writer and historian?

Walker: I was born shortly after the Panthers were formed. I was a year old, just a little over a year old, when Fred Hampton was murdered. I didn’t find out who Fred Hampton was until I was about 19 or 20 years old. And to me, that is a travesty of the public school system, of American history. If I have a role in any capacity, it’s that I don’t think any school kid in this country should not know who Fred Hampton is. I don’t think any school kid should not know what the Black Panther Party stood for. I think every kid who’s receiving free breakfast in schools needs to know where the free breakfast program started. And you know, if I have a role in any of this, it’s just like, ‘hey, man, let me tell you about something that I learned about.’