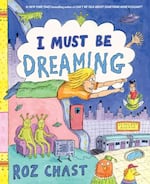

Roz Chast's latest book is I Must Be Dreaming

Bloomsbury Press

Roz Chast’s first New Yorker cartoon was published in 1978, and she has since published more than one thousand. Chast is the author of the graphic memoirs “Going Into Town” and “Can’t we Talk About Something More Pleasant.” Chast spoke about latest book, “I Must be Dreaming” with Dave Miller at the 2023 Portland Book Festival.

The following transcript was created by a computer and edited by a volunteer:

Dave Miller: This is Think Out Loud on OPB. I’m Dave Miller. Roz Chast’s first New Yorker cartoon was published in 1978. She has since published more than 1,000. She’s the author of the graphic memoirs “Going Into Town” and “Can’t we Talk About Something More Pleasant.” Her cartoon collections include “The Party After You Left” and “Theories of Everything.” Her latest book is called “I Must be Dreaming.” Humans have probably been using some of our waking hours to think about what our brains are doing during our sleeping hours since the dawn of humanity, but only Roz Chast could have written this book. It is hilarious, weird, poignant, anxiety ridden and thought provoking sometimes all at once. I talked to Roz Chast in front of an audience at the 2023 Portland Book Festival. [Applause]

Early on in the book, you write, “The fact that dreams exist at all is kind of miraculous.” What’s the miracle for you?

Roz Chast: Well, the miracle for me is that it is such a different state of consciousness from our waking consciousness. Even though putting this book together, I’ve read a lot of theories about why we dream, I think the jury is still out. I don’t think anybody fully knows why. When we sleep, the screen doesn’t just go black and then we wake up and we’re back into this state of consciousness, what that state really is. And it’s kind of like, I mean, you’re definitely yourself and we all are the sort of center person in our dreams, but it’s very different at the same time and nobody really knows why or what it is.

Miller: In one of your dreams, an interior decorator says to you, “Cushions are the juice of the house.”

Chast: Yes.

Miller: And you’ve latched on to that, right? That’s just a part of your world now.

Chast: Oh, yes. Well, my favorite thing in a dream is when an entire phrase sort of emerges. I don’t know if any of you ever saw the Freddie Krueger movies. One of the scariest things in those movies to me or most intriguing, scary in a good way, was when this girl had this dream and he’s chasing her and she grabs his hat and she wakes up and she’s still holding his hat. It’s like the thing has kind of passed from the dream world into the real world. And for me, when an entire phrase emerges like cushions are the juice of the house, it’s like, hoo, hoo, got it. You know? [Laughter]

Miller: Do you remember having conscious thoughts that were anything similar to that? Had you thought about the juice of cushions before, that you remember?

Chast: No, I don’t really think about interior decorating all that much and I don’t really think that much about cushions although the hotel that I’m staying in right now made me laugh. There was such an arrangement of pillows on the bed and it started out with some big ones in the back. Then there were two very big cushions. I hope this isn’t too boring. Then there were three slightly smaller cushions. Then there were four slightly…it was like the cushions kind of moved up until it ended with one tiny cushion and it was just nonsensical. I had to take them all off the bed, of course, because there were so many cushions you couldn’t even get on the bed. It was really weird.

Miller: We could stop this interview right now because I feel like I’ve accomplished everything I want in life. I am mystified and made so angry by those cushions.

Chast: Yes, I am too. I am too. I wanted to complain but who do you complain to?

Miller: I mean not to only make this about cushions but obviously they’re not usable so the only thing you can do is put them on the ground.

Chast: Yes, you put them on the ground.

Miller: You know that everybody else did that.

Chast: So they’re completely like filth cushions.

Miller: I 1,000% agree. To go back to some things in the book. One of the things that I struggled with as I was reading the book is this tension that you’re talking about, that dreams they seem to come from…obviously, they come from us.

Chast: Yes.

Miller: But it doesn’t feel like that you hadn’t had that particular thought before. And there’s all kinds of weird things that we would not have devised ourselves consciously.

Chast: Right.

Miller: So there’s that, but then when I read this book it may partly have been because you illustrated it and I’m so used to your style. But for almost every dream in the book, I think, ah, that’s Roz Chast. I see a sort of a Roz Chastness in them. And I’m wondering if you do, too? If now, in retrospect, you can say, “yeah, that’s me,” for all these things you didn’t consciously devise?

Chast: Oh, I think that our dreams are us. Your dreams are going to be yours. Everybody here, your dreams are going to come from you there. So, yeah, they’re just intrinsically ourselves. But I think that part of the other mystery is that why am I always so surprised? If I’m thinking them up, then (a) why am I surprised? And (b), why would I make up a terrible dream that grosses me out? Like, last night I had a feather growing out of my back and it was like I had to sort of pull the feather out and it sort of hurt and it was gross. And then there was another feather on the other side of it and I had to call the doctor and I couldn’t. Why am I dreaming this? [Laughter] It’s as if I am making up my own dream. I’m like, I’m winning the lottery and then it’s like, I’m in a bakery and everything’s great. And no, I have a feather growing out of my back.

Miller: You have a dream where you read an article about a made up person who is described, I don’t even know how to pronounce this word, “bucephalic.”

Chast: Oh, yes.

Miller: A word I didn’t know. And you write, you didn’t know it, but then you google it after you woke up because you remembered reading the song in the dream and it turns out it sounds like it’s going to be very dirty. It means having a shape like a bull’s head.

Chast: Yes. Yes.

Miller: How do you explain that?

Chast: No idea. No idea at all. Because I think there were some…I don’t know whether it’s Greek [or] Roman, Bucephalus and he had a bull’s head. It was like some God. So this person in the dream and I remember I woke up and it was a bucephalic head. And it was like, I don’t know, there is a term that Freud coined called day residue, where these things that you might not be conscious that are going into your brain - like it’s possible that at some point I must have seen that word and it stuck in my head.

Miller: The beautiful aspect of that is, it’s a reminder that there’s more up there that’s theoretically accessible than we’re than we’re normally aware of.

Chast: Yeah, that’s probably true. Although it sometimes kind of feels like I was checking the storage on my Macbook Air yesterday and it’s like, OK, this much is photos, this much is documents and then it’s like this much system data and it’s like, how do I delete some of that? [Laughter] But you can’t.

Miller: I mean, that system data, I guess for our brains, is just what lets us exist.

Chast: Yes, I think that’s at least what Apple wants you to think because sometimes it does feel like storage is full.

Miller: You’re talking about like a neurological conspiracy theory.

Chast: Yeah, pretty much, along with the pillows. Yeah.

Miller: Can you describe some of your recurring dreams?

Chast: Oh, sure. I think there’s a lot of recurring dreams that I have that a lot of people have. Tooth dreams are very, very common. Tooth loss dreams. I have the classic dream of being back in high school and I don’t know my schedule and I have to go to the office and then I can’t find the office and then it’s like this big, big, big kind of anxious mess. And then at some point in the dream inevitably or very often, I think, “wait a minute, I graduated from high school a long time ago,” blah, blah. [Laughter] And you would think that that would be the kind of epiphany that I would never have this dream again, but you’d be wrong because I do have that dream frequently and I don’t know why. There’s that.

There’s also this classic dream that I don’t know if it happens in other cities in New York, but like you’re in your apartment, which is tiny and expensive, but then suddenly you open a door and there’s like more rooms and it’s really exciting. Or I often have this dream that Manhattan has a neighborhood I did not know about and it usually involves something nonsensical like there’s a beach in Midtown. I remember one, I can still sort of picture it, where there were like tons of windmills and like with these rolling hills and it was just like the Upper West Side someplace.

Miller: To me, one of the Roz Chast giveaways for this is that there’s a beach in Manhattan. You say that there’s coral colored sand and it’s lovely. There are shells here and there. Some of the shells are chipped.

Chast: Yes.

Miller: And it’s like a comedian adding a smart tag to a joke. But your dreaming brain did it. That’s what makes the dream funny.

Chast: Yes. The little chipped. It was like, well, these are really pretty but they’re kind of chipped.

Miller: Yeah. Or your brain won’t let the dream beach be perfect.

Chast: No, that would not be something that I would dream of. No, there’s something wrong.

Miller: You mentioned teeth falling out which people have been writing about having dreamt for a long time and a lot of theories about what that means.

Chast: Yeah.

Miller: But dentist dreams I hear less about and you’ve had a lot of them just in this book there are like three or four dentist dreams, all of which are fantastic. Do you have a favorite of them?

Chast: The one with Kissinger.

Miller: Please, can we hear that one?

Chast: In the dream, I was going in to see the dentist and Kissinger was walking out and he was looking at his Blackberry, I remember, and he looked kind of worried and when I went in to see the dentist, the dentist was kind of sad. And he said, “I don’t think I’m going to be able to work on you today because my hands are still too sore from the stress of working on Kissinger.” And then he held up his hands and they looked kind of like all red and kind of raw. And then there were like other aspects, but that was like a very fun, interesting part of that dream. It was like, I don’t know. I don’t think about Kissinger. Why was he in my dream? I have no idea. I don’t like him. I don’t think about him.

Miller: You said you also don’t think that much about Danny Devito, but he was in one of your dreams. A super lovely one.

Chast:. Yes. Well, I have to tell you about that dream because it was really wonderful. I had this dream that I included in the book and I love his acting. I think he’s the greatest. He’s really funny. I love “It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia.” I’ve loved him for decades. I just think he’s really charming and hilarious and just fun to watch. And so I had this dream but I don’t generally think about him that much. So I had this dream that he was lying on my lap with his head in my lap and looking up at me with adoration and I was thinking in the dream, like, I’m not in love with him, but it’s nice to be adored so maybe this will work out. But this crazy thing happened a couple of weeks ago. I’ve been doing some interviews for this book so I was in New York and I was doing an interview for NYC and the person who was on right before me was Danny Devito. And he was with a group of people and I was with a person from my publisher and somehow, I don’t remember who showed it to him, but they showed him the page in my book where I had dreamed about him and he really liked it. And then he hugged me and we were hugging and it was like this is the weirdest thing ever. And then he signed it, “Oh, so nice. Love, Danny Devito.” So when I do my slideshow, I show that page with his like scrawled kind of thing on it because it was just like a life that imitated a dream. It was really funny.

Miller: One of so many chapters in the book that I love is, I think you call it boring dreams.

Chast: Every day.

Miller: Oh every day. OK. But so instead of sort of truly fantastical, weird things which are possible because we can make anything happen, you have a bunch where very little happens. In one of them, you’re shopping for shoes and you need insoles. They don’t have them. You get them anyway. My favorite part is that the credit card is shaped slightly differently. It’s not a rectangle. It’s the square. End of a dream.

Chast: Yeah. Well, and it has a wheat field on it.

Miller: Oh, I missed the wheat.

Chast: Yeah.

Miller: Oh, the picture on the credit card is a wheat field.

Chast: Yes, it’s a square credit card and it has a wheat field on it.

Miller: OK. This is a good chance to talk about how you remember these things. I mean, that is a tiny detail. We’re not just talking about the shape of a credit card but the logo on it. So what’s your process for remembering dreams?

Chast: I have a notepad by my bed and I do find that if I don’t jot stuff down immediately, dreams are just notoriously ephemeral. They just kind of go wooooooo. But sometimes I tell them to my husband or something, but you have to try to grab them right away or at least for me, they completely just disappear.

Miller: How long have you had a kind of illustrative dream journal?

Chast: Well, I have gone in and out of it. I started actually doing this kind of illustrative

dream diary, I think it was about 2019, because I was working on another book and I was running into troubles with it and not really that into it. And one of the things I was doing while sort of stalling, not working on the book I was supposed to be working on, was drawing up dreams. And the first one that I did, I remember was my mother, the dream about OJ Simpson’s glove and this guy named Bissell. And the only thing I could think of with Bissell is that there’s a drug store in my town, Bissell’s Drugs, but this had nothing to do with that. It was just a guy named Bissell who had come into possession of OJ Simpson’s glove and wanted to rent it out for parties. [Laughter] And my mother was upset about this and she said the glove should be in a safety deposit box.

So it’s just completely nonsensical and, and I thought this was so funny and I’m going to draw this dream up and I’m going to post it to Instagram because it’s the only social media thing I do because it’s visual and I like it. So then I got into drawing up a kind of cartoonifying the dreams a little bit. I’m not going to illustrate every little thing that happened in the dream. I’m going to take the dream, edit it a little bit, shape it a little bit but not make anything up, just kind of put it into a cartoon…

Miller: We call them filets of dreams.

Chast: Filets. Yes, they’re the best parts.

Miller: Yeah, very fancy.

Chast: Yes. And then there’s a little sprig of parsley on the top to let you charge an extra like $5 for that. But I got really into doing that. So, at some point I did kind of go to my editor and I said I was thinking, maybe I could like to get out of doing that book I don’t really want to do and I really would rather do this because I have always been interested, since I was a kid, in dreams. And when I was a teenager, I kept and still have these dream diaries and boy, my memory was a lot better then. It was just pages and pages and pages.

Miller: I’ve never had the diligence to have a dream journal or diary, but I’ve heard that the process of doing it, builds upon itself and you get better, the memory dream muscle actually gets stronger. Has that been the case for you?

Chast: Absolutely true. Yeah. The more you get into a habit of it. Sometimes people say, “I don’t dream” and I think that’s just bull-. You’d completely dream. But like if you don’t think about them, if you’re not in the habit of remembering your dream, it’ll just disappear.

Miller: Why do you think they disappear? What’s your theory for why they’re so evanescent?

Chast: I think it might be something that’s built in for survival that probably if your dreams were too much a part of your daily life, if you were switching in and out of that too much, maybe I don’t know, the old saber toothed-tiger idea, that it’s probably better that maybe when you first wake up, if you think about your dreams fine. But then when you have to fight off the saber toothed-tiger, it’s maybe…

Miller: So it kind of like that preservation is sticking with the real world.

Chast: Probably.

Miller: Not getting lost in the dream world.

Chast: Probable. I don’t know. I mean, that’s just the thought.

Miller: I’ve always been frustrated by the way they just blow away because it feels unfair but I guess the flip side is to think about it as like a beautiful sandcastle before the tide comes in. You had this experience. Maybe you remember, maybe you don’t. But it’s gone and the value is actually that it might just disappear.

Chast: Yes. But I mean, there’s so many different ways to think about them. I mean, there were cultures that thought that the dreams were predictive, that you could read what was going to happen in the future from what was happening in your dreams. There are people whose cultures believe that it actually had something to do with healing your soul. Of course, Freud believed that if you had fears or you’re neurotic about things, that you could work with your dreams and maybe solve some personal life problems through that, get insights into your own personal psychology. Jung, of course, believed that they were a way to connect with the collective unconscious.

Miller: So, of those two, those big 20th century western dudes, which side are you more on: collective unconscious or sort of inner workings in and out?

Chast: I would go with Jung.

Miller: Why?

Chast: Because I do think that there’s more than just our…this gets into a little bit woo-woo for 10 o’clock in the morning, but...

Miller: Imagine it’s 10 p.m.

Chast: I do think that there’s more to consciousness than just our own individual sort of separate selves. I think there is some sort of collective unconscious.

Miller: Is there a connection for you between dreaming and spirituality?

Chast: The word spirituality actually gives me the complete heebie jeebies [Laughter], but I do know sort of what you’re talking about and aside from my own personal heebie jeebies from that…

Miller: Is there a word you like more? [Laughter]

Chast: No. It gets into that stuff that’s very hard to talk about without sounding completely [bleeped word]. I know we’re on the radio and stuff like that.

Miller: We’re on the radio in the future.

Chast: Oh OK. You can just call it like “malarkey.” [Laughter]

Yeah. I do think that dreams connect to some part that is…Freud hated what he called the swamp of mysticism that Jung was getting more pulled towards.

Miller: You say that was a specific dig towards Jung?

Chast: Yes. It was a real dig. That was what caused their sort of schism. Jung was a protege of Freud until that point, but I think that dreams are probably the closest way without drugs that we connect to something that’s beyond just our personal way of looking at our egos.

Miller: You write about something called “Madam Fu Fu’s Lucky Number Dream Book” which…

Chast: It’s real.

Miller: Well, I googled it because I thought, well, this is a great Roz Chast invention.

It is completely real, “Madam Fu Fu’s Lucky Number Dream Book.” It can be purchased, as of last night, for $3 plus $10 shipping and handling. Did you buy it?

Chast: I did.

Miller: Can you describe it?

Chast: Oh, it’s great. It’s very, very specific, but it’s kind of like if you dream about something like green peppers, then you should bet on these numbers.

Miller: I have that number. I wrote that one. Green pepper is 418.

Chast: Green pepper is 418. Red pepper is something else.

Miller: Red pepper is seven. I only wrote four of them down. But you guys…

Chast: That’s so funny.

Miller: Red pepper is 763. So, if you dream of eating prunes, then the lucky number for you, which means you should then use it for a lottery, is 286.

Chast: OK.

Miller: I have one more, if people want it. You probably can guess this. 511: stinky feet.

Chast: Stinky feet. Yeah.

Miller: So how would this have been used? Do you think it really was?

Chast: I have no idea. I just kind of liked it. I don’t know.

Miller: You have a whole chapter that’s about dream theorizing and one of them is the screensaver theory.

Chast: Yes.

Miller: What’s that?

Chast: Oh, the screensaver is just that it kind of keeps your brain sort of going so that it doesn’t shut off. Because when you’re sleeping, I guess, I don’t know, it’s just basically what your screensaver used to do for your computer where we’d keep things kind of running while it did its little internal housekeeping or whatever.

Miller: I forget the guy’s name, but there’s a Finnish neuroscientist who has an evolutionary idea, which I don’t like at all.

Chast: Is he the one that was like a re-primitive like in the survival instinct rehearsal? So, basically in your dream, you are rehearsing for a bad situation so that when you encounter it, you are more able to deal with it.

Miller: Exactly. And it’s not like most of us are dreaming regularly of saber-toothed tigers chasing us. The dreams are so much weirder that it’s hard to see how they would be.

Chast: Right. What does the Bissell glove thing have anything to do with my survival or like this wheat field credit card? I mean, buying bed slippers. It’s like nonsense. It’s so that I have that kind of relentless scientific reason for dreaming, I think it might be part of it. I think that all of these things are true to some extent, but there’s not just one reason. But I think some people like to think that there’s one reason that makes them feel better if they can say “no, that’s the reason and all the rest of it is malarkey.” [Laughter]

Miller: Do you mind if we just cut you saying malarkey and use instead of a beep from now on?

Chast: Oh!

Miller: When someone says a swear word, we’ll just have you saying “malarkey?”

Chast: I could just…malarkey. Yeah. Go ahead. Go ahead. [Laughter]

Miller: Can you describe the temples that ancient Greeks set up for dream healing?

Chast: Yes. These were called asclepieions and they were special temples because they believed there would be clues within dreams to help you with your life - physical problems, mental problems, emotional, financial. And it was either the dreams were done by the person who wanted the answers or you could hire a proxy and you would go to these temples and there were all these rituals. You didn’t just go in and well this is my hotel room, I’m going to sleep. Throw the pillows off the bed. No, there was fasting and then you drink these things and then [took a] hot bath and a cold bath and there were all these rituals. And then you would go to sleep and then the dreams would be interpreted and answers to the person’s problems would be found within the dreams. But they were special, special temples.

Miller: I bet I’m not the only person to make this connection. I’m not sure if you know about Oregon’s relatively recent supervised Psilocybin law. Oregon voters a couple of years ago were the first state in the nation where it’s happening now. You can go legally and I won’t go through everything about the law, but basically you can have the supervised legal use of Psilocybin and it’s not technically for therapy, but that is essentially how people are using it.

Chast: Yes.

Miller: It made me think that it sounds very similar to what you were describing with ancient Greeks and dreaming and it just made me wonder and then obvious connection here is that like dreams, psychedelics unlock some less conscious part of the brain and give you sort of narratives inside your own head that are different than what you’d have if you hadn’t taken them or weren’t sleeping. Are you at all interested in psychedelics in this context?

Chast: Oh, very much so. Absolutely. I wrote about it a little bit in the book when I was…

Miller: When you were 16?

Chast: When I was 16, 17, 18, I did take LSD a few times and it was very interesting. Very, very interesting. And I think that dreaming and that state of consciousness, they’re not too far apart. One of my most vivid memories was of not knowing whether I was dreaming or whether I was awake and that’s a very unusual feeling. I mean, especially being awake because when I’m awake, I’m pretty sure I’m awake. Sometimes when I’m dreaming, I get confused, especially with lucid dreaming. And I wrote up a couple of those dreams. Lucid dreaming, when you are aware that you’re dreaming in a dream, but then sometimes, like I’ll be aware I was dreaming and then I’m still dreaming, but I think I woke up. So there’s more confusion in that state. But, yeah, it’s definitely something I’m interested in.

Miller: Can you imagine, “The Roz Chast Book of Magic Mushrooms?”

Chast: Uh…yeah. Yeah, yeah, yeah. [Laughter]

Miller: I love those noises. The lucid dream reminds me of something you say in passing, that online, there are people who will tell you how to optimize your dreams, which you say is a stupid idea. So what are they offering? And what’s stupid about it?

Chast: Oh, I guess it makes your dreams even better. I think part of the thing that’s interesting about dreams is kind of letting them take you where they’re going to take you. And I don’t know, sometimes it just seems so tiring to make every malarkey-ish minute of the day optimized to see what you can squeeze out of it. How can you be a better you? Why this cardboard isn’t good enough for me! It should be… It’s just, oh God, it gets so tiring. So dreams are like one of these times where you can just kind of go. Well, let’s see where we go tonight.

Miller: As someone who asks questions for a living, I’m sort of allergic to questions I feel like I ask all the time and one of the most common ones for creative people is where do you get your ideas from? But this book, it sort of casts that question in a new light, and in a really interesting light, because you write so much about the sometimes mysterious connections between creativity and dreaming and sometimes the more obvious ones. If you get an idea that that might turn into a cartoon directly from a dream, that’s not exactly a mystery. It’s just, you may not know where the idea came from, but it got you in a dream. But I’m wondering what working on this book has shown you about your waking creativity.

Chast: Well, the quote from Murakami that I included where he said that for him, “writing is a little bit like dreaming,” he put into words something that I feel that I do when I’m thinking of cartoon ideas because what I do for work is a very strange thing. It’s like I go up to my desk and I’m faced with what Bill Woodman, a wonderful New Yorker cartoonist from decades ago, called the blank piece of paper, The Blazing Island of White. And that’s what you’re sort of faced with. I mean, I do have my ideas that I’ve gotten during the week written down on a piece of paper, but most of what I do is I’m sitting and I’m thinking and I’m doodling and I’m letting all of these thoughts kind of flow through my head. And so it’s a very strange kind of process. So, I don’t know, I guess I felt sort of validated in some ways by the Murakami quote because I thought, yeah, that’s pretty much what I do. I’m sitting and I’m thinking and letting my thoughts kind of go where they will.

I mean the worst is just sort of thinking I am going to think up the funniest idea anybody has ever had. I mean, it doesn’t work like that. That’s like a recipe for disaster for me. But sometimes when I’m sort of thinking, something funny will happen. I don’t know, some odd juxtaposition of words or I’ll suddenly remember something or the way the pillows looked on the bed and the way they kind of came to a point with the one tiny pillow and stuff like that.

Miller: Has that changed for you over the years? You’ve been doing this for, for a number of decades now. Is it easier to face that? What was it…

Chast: The blazing island of white.

Miller: Yeah. Now, because you know that over and over in the past, your brain has done something and an idea has come. Is that something you can trust now or is it as terrifying as it sounds?

Chast: No. It’s horrible. It’s over and over. It’s, in some ways, worse because now I’m more aware of all this stuff - like my cartoons, I don’t want to do that. I did that already. And you get more critical and it gets worse. And you also become more aware of sort of, I don’t know, not that it’s pointless but maybe a little bit. When somebody asks me sometimes, like “my kid wants to be a cartoonist, what advice [do you have]?” I always say if they can do anything else, then they should do that thing. [Laughter] This is really for people who feel kind of compelled to do this.

Miller: And you’ve been compelled to do this since you were a teenager, right?

Chast: Yeah. Well, I drew from the time I was little, like before I could write. And I never ever thought about not drawing. I just always drew, but when I was around 12 or 13, I started thinking about being a cartoonist.

Miller: To go back to the cushions, the pillows, have you made a cartoon about those before?

Chast: No.

Miller: So when you have a fun idea - which maybe doesn’t just please me as somebody who has thought a lot about the diminishing zone of pillows, but probably other people have experienced that - how would you test out whether that’s a fertile enough idea to be a panel or more than one?

Chast: I’ll doodle it. I’ll draw it either on paper. I have an iPad. In fact, I’ll probably draw it out. And the one thing about the New Yorker, the system that they have, that’s so great is that you don’t just submit one cartoon a week. That would be sort of sickening in a way because you’d feel like it would have to be really good and then that immediately kills any spontaneity. You submit a group of cartoons every week. So some people it’s four, some people it’s six, some people it’s 10. I usually submit six or seven. And yeah, that will probably will go into the batch, maybe next time I submit.

Miler: Pillows?

Chast: The pillows, yeah.

Miller: So, but when you draw it out, you don’t just do visual jokes. I mean, your words are..

Chast: Sometimes visual, like this could be a visual one.

Miller: With a title?

Chast: Yeah. Right.

Miller: So, I guess I’m wondering how you decide something is good enough for yourself?

Chast: If it makes me laugh or seems funny.

Miller: You can laugh at your own words.

Chast: Occasionally, but I might not laugh out loud. Sometimes I do. Sometimes something will make me laugh out loud.

Miller: That sounds fantastic to be able to laugh at…I mean, you’re making work that makes the rest of us laugh and it makes me happy to think that sometimes you can actually laugh as well.

Chast: Yeah. Sometimes, but sometimes it’s like eh huh… [Laughter]

Miller: But that means it’ll work.

Chast: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah.[Laughter]

Miller: What if it doesn’t work?

Chast: Then if it’s really bad, bad, it goes into the trash. If it’s sort of semi-bad, I have a sort of pile of, I may rework this later kind of thing. So there’s just like a whole, like, levels of badness, basically.

Miller: One of your dream fragments, you call them ‘”The Ones That Got Away,” is this: “A cult of fat men in France who dress like Liberace but sound like Johnny Cash.”

Chast: Yeah. And there’s a couple of pages in the book of this. I’ll just remember like one little bit of a dream, but that was a good one.

Miller: But I’m trying to figure out is that cartoonable or is it just hilarious but can’t it be turned into two dimensions in a way that works for you?

Chast: Well, it was fine to include in that spread.

Miller: I guess I’m thinking about it by itself in New Yorker.

Chast: No, I don’t think so.

Miller: Why not?

Chast: I don’t know.

Miller: You have a chapter about nightmares. To me, the most powerful and poignant cartoon in the whole book is somebody in that chapter hands you a phone and it’s your mother who’s been dead for a number of years. She’s on the other end, weeping and wailing

Chast: Yeah.

Miller: And then you actually woke up. It’s not a scary nightmare. It’s just tremendously sad and sort of traumatizing. How often do you dream about your parents these days?

Chast: They do come up. Definitely not every night, maybe every couple of weeks.

Miller: In that tone or in a different way?

Chast: In different ways, but they’re almost always old and I’m almost always an adult

Miller: So the dream versions are closer to their final years than, say, you as a child and then them in their thirties or forties.

Chast: Yeah. Definitely. I can’t even think of a dream I’ve had of them where I’m a child and they’re younger.

Miller: Another cartoon in that nightmare chapter seems like it was scary in the moment, but it is just absurd and quite funny now. It’s “The Pringle.”

Chast: The pringle.

Miller: Can you describe “The Pringle?”

Chast: This was like one of those dreams. You think, what is going on in my subconscious? So I had this dream about this horrible creature that looked a little bit like a kind of horrible weasel mixed with a naked mole rat. And it was like a stretched out creature. I drew it immediately when I woke up and it was called a pringle like the chip [Laughter]. And I woke up from it and my husband said that I was windmilling my arms around and he said, “you were moving your arms around like a marionette.” And I don’t even know what that means, but I woke him up. I was running away from the pringle.

And the thing about the pringle that I learned in the dream is that it’s a very bad omen. And if you see a pringle in your house, you have to leave the house and you can never come back. So it was really scary. It was terrifying in the dream and then I woke up and it was like, this is ridiculous. This is hilarious.

Miller: Actually, I think that’s the only page in the book where we see one of your dream journal jottings, in addition to the fully realized cartoon.

Chast: Yes.

Miller: And one of my favorite things about it is you actually include a little thing for scale. You wrote “two-feet long.” So we see the pringle…it’s not, you know, six inches.

Chast:. It’s a horrible stretched out body with this little naked mole rat head.

Miller:. Do you have work anxiety dreams?

Chast: Oh, yes. Oh, lots.

Miller: So, what is work anxiety for a cartoonist?

Chast: Oh, just going into the New Yorker and I’ve forgotten to bring my work in and they’re a little bit like related to the high school anxiety sorts of dreams.

Miller: Being unprepared?

Chast: Unprepared, yeah.

Miller: I have those regularly, where I’m all of a sudden here and I don’t know who I’m talking to or who they are, what I should ask.

Chast: Yeah, I could imagine that. I think that probably everybody I know…in my reading about dreams, I think Aristotle said that people do dream what they’re in their professions.

Miller: You wrote, podiatrists must dream of bunions.

Chast: Oh bunions, yeah. Maybe they have bunion anxiety dreams or something.

Miller: You mentioned the pillow dream, which I promise that this is the last time I’ll bring that up. Have other recent dreams that tickled you? I mean, other recent dreams that if you’d had them before you wrote the book you might have put them in?

Chast:. Oh yeah, I mean, I can’t remember any right now, but I think it’s like an ongoing thing. I was talking to a fellow cartoonist, a person who makes books about how there must be some like one of those long German compound words for the regret that you have once you can’t add anything into the book or change anything. [Laughter] So there’s definitely that.

I know that there is this word that I love, torschlusspanik, which is door shutting panic. And like when something closes the door shuts and now you can’t make any changes. And it’s like that’s when you think of all the changes that you want to make.

Miller: If you could change something about dreams, have the power to change the way you dream or how you dream, would you? Or is that in the realm of optimization that you resist?

Chast: I think that’s the optimization. I kind of like the fact that I don’t control them, that it’s kind of like giving myself over to something else and kind of going with it.

Miller: I was thinking about this as I read the book, what if you could meet people and dream and say, “hey, let’s go fly around together at 11 pm tonight” or “let’s go do tuna salad sandwich tasting?”

Chast: Oh, you mean in a dream?

Miller: Yeah.

Chast: Well, one of my kids and I used to try to do that because she was also interested in dreams the way I was and we would try to meet on the astral plane. But it never, never worked.

Miller: Why do you think that talking about dreams gets such a bad rap? Imean, it’s famous. People say dreams are boring obviously, but we know they’re not. Why do you think we’re told not to talk about them?

Chast: I really don’t know because I find that a lot of things that people talk about to me is very boring. Golf is very boring. I mean, it’s painfully boring, but people like to talk about it.

Miller: Are you often subjected to golf talk?

Chast: I’m not into golf talk. No.

Miller: No, but are you around it?

Chast: Oh, sometimes yes. Or people talk about their yards or something or gardening. Like, I don’t care, I don’t care about any of that. They talk about their exercise. Like, ugh! [Laughter] You know, there’s so much that people talk about that I find extremely dull.

Miller: So why are dreams singled out?

Chast: I don’t know. I honestly don’t know because I think that they’re very interesting. Well, Heraclius, a Greek philosopher in 500 BC, said that we are all in this same world, but “in dreams, we all turn to a world of our own.” So maybe it seems to some people to be too egocentric or too selfish, too personal. But to me, I feel like since this is an activity that we all do, it’s not so bad to talk [about]. I’m not a big fan of when people monologue about anything. It could be like the most interesting topic in the universe, but if somebody is just going on and on and on and on and on, then it’s boring.

Miller: Has writing this book and going on this book tour opened the floodgates for people to talk to you about their dreams?

Chast: No, I wouldn’t call it floodgate. People talk a little bit about [it]. But most people, I think, are sensibly understanding to not stand for like half an hour and “then, and then, and then and then…”

Miller: Especially if they’ve heard you say you don’t want a monologue. Roz Chast, it was a pleasure talking to you. Thanks very much.

Chast: Thank you. Thank you!

Miller: That was the one and only Roz Chast in front of an audience at the 2023 Portland Book Festival.

Contact “Think Out Loud®”

If you’d like to comment on any of the topics in this show or suggest a topic of your own, please get in touch with us on Facebook, send an email to thinkoutloud@opb.org, or you can leave a voicemail for us at 503-293-1983. The call-in phone number during the noon hour is 888-665-5865.