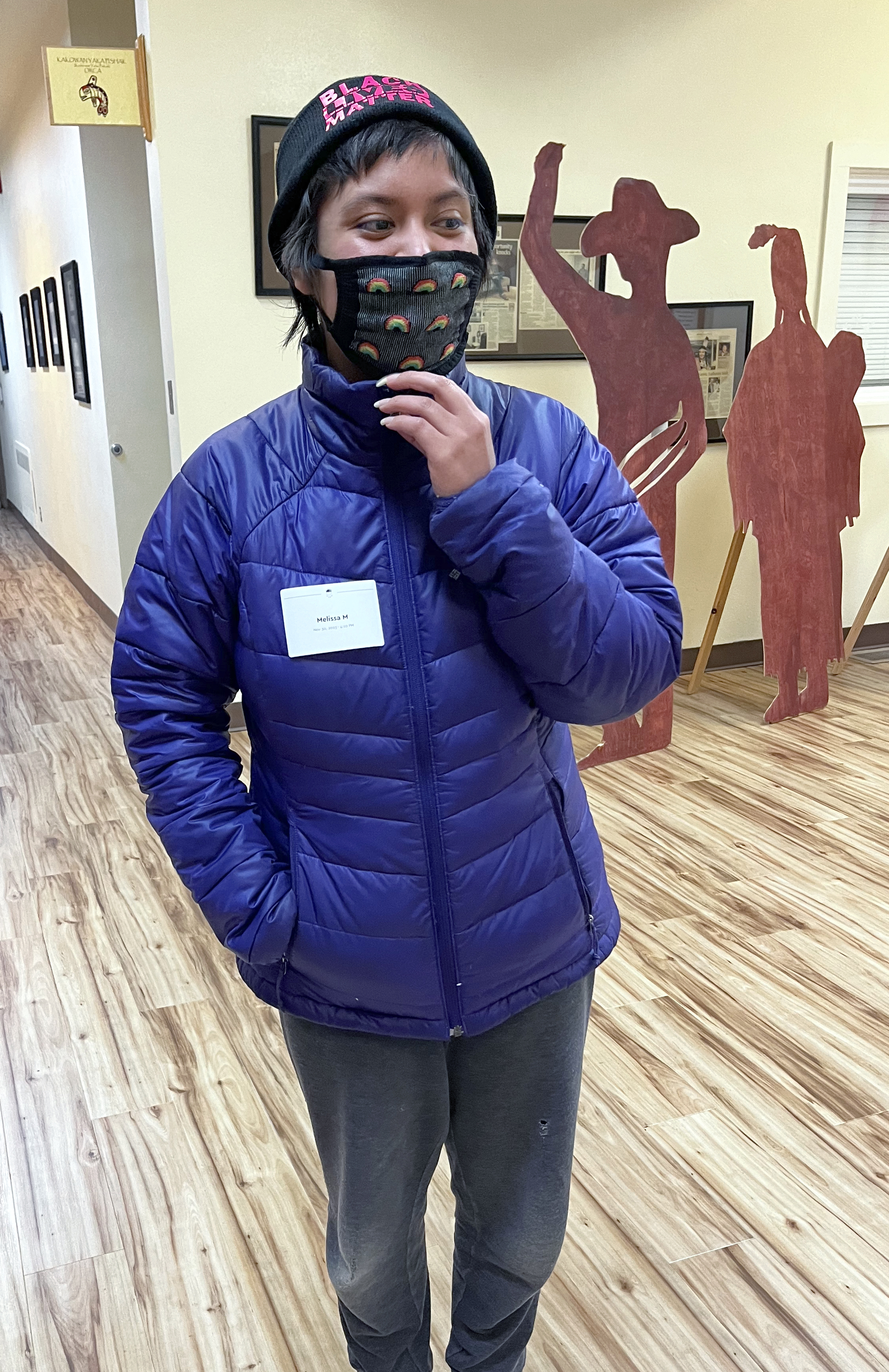

Melissa Juans-Munoz is participating in a statewide pilot program that gives young adults who have experienced housing instability $1,000 a month. Nov. 30, 2023.

Tiffany Camhi / OPB

This is Part 3 in series of stories looking at Oregon’s unsheltered young adults — learning who they are and what forces are working against them. See Part 1 and Part 2.

An ideal career for Melissa Juans-Munoz would combine their love of supporting other people with honoring their Indigenous roots in Central and South America.

“I do like to help people process through hard stuff,” said Juans-Munoz. “I like being there on their healing journeys, as a guide.”

But Juans-Munoz has had their own hard times. The 22-year-old grew up in and out of foster care for about nine years. In 2019, Juans-Munoz began couch-surfing at friends’ homes and entered Portland’s Homeless Youth Continuum. Juans-Munoz’s limited income also stood in the way of them pursuing work in a field that could align all of their interests: a psilocybin facilitator.

“I feel like it’s a job that is close to my ancestors,” said Juans-Munoz, whose family is from the Mayan Q’anjob’al Nation of Guatemala.

Psilocybin facilitators are a new occupation in Oregon, created by the passage of Ballot Measure 109 in 2020. The therapy has roots in the practices of Indigenous people of South America.

Psilocybin facilitator training programs are expensive though, costing up to $12,000 in tuition and fees. That has always seemed out of reach for Juans-Munoz.

But last year they started receiving no-strings-attached cash payments of $1,000 a month through a statewide pilot program, called Direct Cash Transfer Plus. In addition to the $1,000 a month for two years, young people also have access to a one-time $3,000 “enrichment fund.”

It’s money participants like Juans-Munoz can spend or save however they want. With this money, Juans-Munoz can now see a more realistic path toward their dream job.

“Part of me being able to get [the training and license] is also having the funds,” Juans-Munoz said. “The money has catapulted my journey.”

The payments are a part of a two-year statewide pilot program for homeless youth. Young people participating in the anti-poverty program say the extra money has helped them meet their basic needs. And many, like Juans-Munoz, say it’s also helping them realize a better future for themselves.

Oregon is one of a handful of places in the nation experimenting with giving cash without restrictions to homeless youth.

Besides qualifying as a young person who has experienced homelessness, Oregon’s only other requirement is for participants to confirm they received the money each month. That’s it — no budgeting or accounting for how the money is spent is required.

The pilot program, which is entirely funded by the state’s general fund, is one of several recent investments in Oregon’s Youth Experiencing Homelessness Program. Including the cash payments to young people and administration costs, the direct cash transfer pilot costs just over $4.4 million to operate in the current biennium.

The state partnered with the nationwide homeless youth nonprofit Point Source Youth to bring direct cash transfers to Oregon. Anjala Huff, a senior director at PSY, said many of the government funding streams that go towards ending youth homelessness have tight rules regarding how the money can be spent. The process can be further complicated by sending money through community based organizations. That’s not so with direct cash transfers.

“What we decided to do is look at cutting out the middle person,” said Huff. “The cash is taken from the funding source and given directly to young people. They’re able to use it as they deem necessary.”

Three youth homeless organizations in the state are facilitating the pilot, which has more than 100 participants overall. Participants began receiving payments in March 2023. Portland’s Native American Youth and Family Center is operating the largest cohort of 74 youth. Nearly all of the youth in NAYA’s program, Juans-Munoz included, identify as people of color. More than a third of the group identify as Indigenous.

Though there are very few requirements for the program, participants are encouraged to take advantage of additional resources offered by the homeless youth organizations running the pilots. Adrianne Jorgensen is one of two staff members at NAYA dedicated to the direct cash transfers program. She helps youth find housing and learn the basics of being a good tenant. Her colleague teaches financial wellness and helps participants create budgets or build credit.

“[The program] is very low barrier,” said Jorgensen, who has also experienced homelessness. “It is really meant to get young people housed, first and foremost, and secondly to let them learn financial autonomy.”

Jorgensen said many of the participants choose to engage in the additional services provided, even though it’s not required.

NAYA's youth housing navigator Adrianne Jorgensen (left) and Melissa Juans-Munoz discuss other community resources available to direct cash transfer participants. Nov. 30, 2023.

Tiffany Camhi / OPB

Direct cash transfers for youth have roots in universal basic income, an anti-poverty intervention that provides regular cash payments with no restrictions to communities. The idea has grown in popularity throughout the U.S., with several cities launching their own pilot programs. Early research has shown that when given the no-strings attached cash, people mostly spend the money on services and food. Studies have also shown an increase in mental well-being for participants.

The idea has received significant push back too, with some people equating it to a handout rather than a social service effort. A 2020 Pew Research Center poll found that a majority of adult U.S. citizens oppose universal basic income.

Point Source Youth is in the process of evaluating the direct cash transfer pilots it helps run, including Oregon’s, to compile baseline data on outcomes. PSY’s Huff said the organization would like to make the program a long-term intervention, but it still needs the data to prove it works.

Baseline state data shows nearly two-thirds of youth participants in the program have been housed since the beginning of the pilot. Some young people were already in the process of getting housed when the program started.

A good portion of the money Juans-Munoz has received so far has gone towards basic needs, such as groceries. Juans-Munoz also bought items to make their Northeast Portland apartment feel more like a home. They bought a bed frame, pictures for their walls and a table. They also spent money on their family, purchasing a cell phone for their 11-year-old sister.

“It does make a world of difference,” said Juans-Munoz of the additional money. “And it makes me feel better when I can help my family too.”

Program participants in Central Oregon, run by Deschutes County’s J Bar J Youth Services, share similar experiences. Dakota, who is 24, used part of their money to buy a used car from a family member. Having their own vehicle has made their life easier.

“When you’re dependent on other people things can go awry: you miss appointments, you have to reschedule or you have to call for an Uber because you’re stranded and that bleeds money,” said Dakota, who preferred not to include their last name for safety reasons.

J Bar J’s direct cash transfers cohort includes 35 young people. All of them were unhoused when it began. With the help of cash payments and other housing assistance, 23 youth are now in some sort of stable housing. Dakota is one of them.

“Most of this money has gone towards long-lasting sustainable things for people like housing, a car, or paying off long term debts,” said Dakota, who has also been able to put some money into savings. “It’s things that everybody would do if they got money handed to them.”

Now that Dakota is not focused on surviving day to day they can think more about their future. This year they plan on going back to school to finish up a degree in computer information systems.

Melissa Juans-Munoz knows these payments won’t last forever. Oregon’s direct cash transfer payments are set to end after March 2025. But Juans-Munoz is hopeful that by the time the program ends they will have made some headway into a job they love.

They are preparing to take the GED test, taking remedial math classes at Portland Community College.

“You have to have your GED or high school diploma in order to do the [psilocybin] facilitator training program,” said Juans-Munoz, who dropped out of school in the 10th grade. “Now I’m gonna get my GED and the direct cash transfer funds bring the financial supportive component to it.”

Juans-Munoz would like to see the program stick around for other youth experiencing homelessness. They said its existence is proof that there are solutions to some of our biggest problems.

“I think this is a really big, huge beacon of hope,” said Juans-Munoz, of direct cash transfers. “It’s helped me believe more in my dreams of making collective change and working with people to demand getting our needs met.”